When Korean Students Go Abroad to Understand Korea: KARSI's Vietnam Winter Art Residency

Why the Best Way to Learn About Korean Colonial History Is in a Hanoi Art Gallery

There's something profoundly disorienting about standing in a French colonial mansion in Hanoi, surrounded by Vietnamese contemporary artists, and suddenly understanding your own Korean identity more clearly than you ever did in Seoul.

This isn't poetic license. It's the core insight behind KARSI's Vietnam Winter Art Residency program—a two-week intensive that partners with Chau & Co. Gallery to transform students into practicing artists while they grapple with one of the most uncomfortable parallels in Asian history: Korea and Vietnam share remarkably similar colonial wounds, just inflicted by different empires.

the Vietnam VOLUNTOURISM Industrial Complex

Before we explain what our program is, let's be brutally honest about what most Korea-Vietnam "educational programs" or “exchange programs” between Korea actually are: thinly-veiled neo-colonial tourism that exploits Vietnam's lower cost of living while packaging superficial activities as meaningful cultural engagement.

You know exactly what we're talking about. The programs that send Korean students to "volunteer" at Vietnamese orphanages for a week (never mind that these children don't need a rotating cast of teenagers who can't speak Vietnamese disrupting their routines). The "service learning" experiences where you build wells or paint schools—work that local contractors could do better and that actually takes jobs away from Vietnamese workers, but hey, you get great photos for your college application.

The fake NGOs that exist primarily to generate credentials for Korean students. The "cultural exchange" programs that consist of visiting tourist sites, eating Korean food in Hanoi's Korean district, and maybe doing a token craft activity with local students before returning to Korea with tales of having "helped Vietnam."

Here's the uncomfortable truth: most Korean educational programs treat Vietnam as a neo-colonial object—a convenient, cheap backdrop for Korean students to accumulate resume credentials. The currency exchange rate means Korean money goes far, so enterprising operators have built an entire industry around packaging Vietnamese poverty and development needs into college application material for Korean teenagers.

The really insidious programs are the ones that recognize, dimly, that Korea and Vietnam have historical connections—but then reduce those connections to "we're helping Vietnam develop like Korea did" or "sharing Korean success with our Vietnamese friends." This framework positions Korea as the developed mentor and Vietnam as the developing student, completely ignoring that Vietnam has its own sophisticated intellectual and artistic traditions that might actually have something to teach Korean students.

KARSI's approach is fundamentally different because we treat Vietnam as an intellectual and inspirational partner, not as a development project or a photo opportunity.

The Parallel You Never Knew Existed

Here's what most Korean students don't learn in history class: while Japan was colonizing Korea (1910-1945), France was doing essentially the same thing to Vietnam (1887-1954). Both countries experienced systematic cultural erasure, forced assimilation, resource extraction, and the peculiar psychological damage that comes from being told your own culture is inferior. Both emerged from colonialism into devastating wars that split their nations. Both spent the late 20th century rebuilding national identity while navigating American influence and rapid modernization.

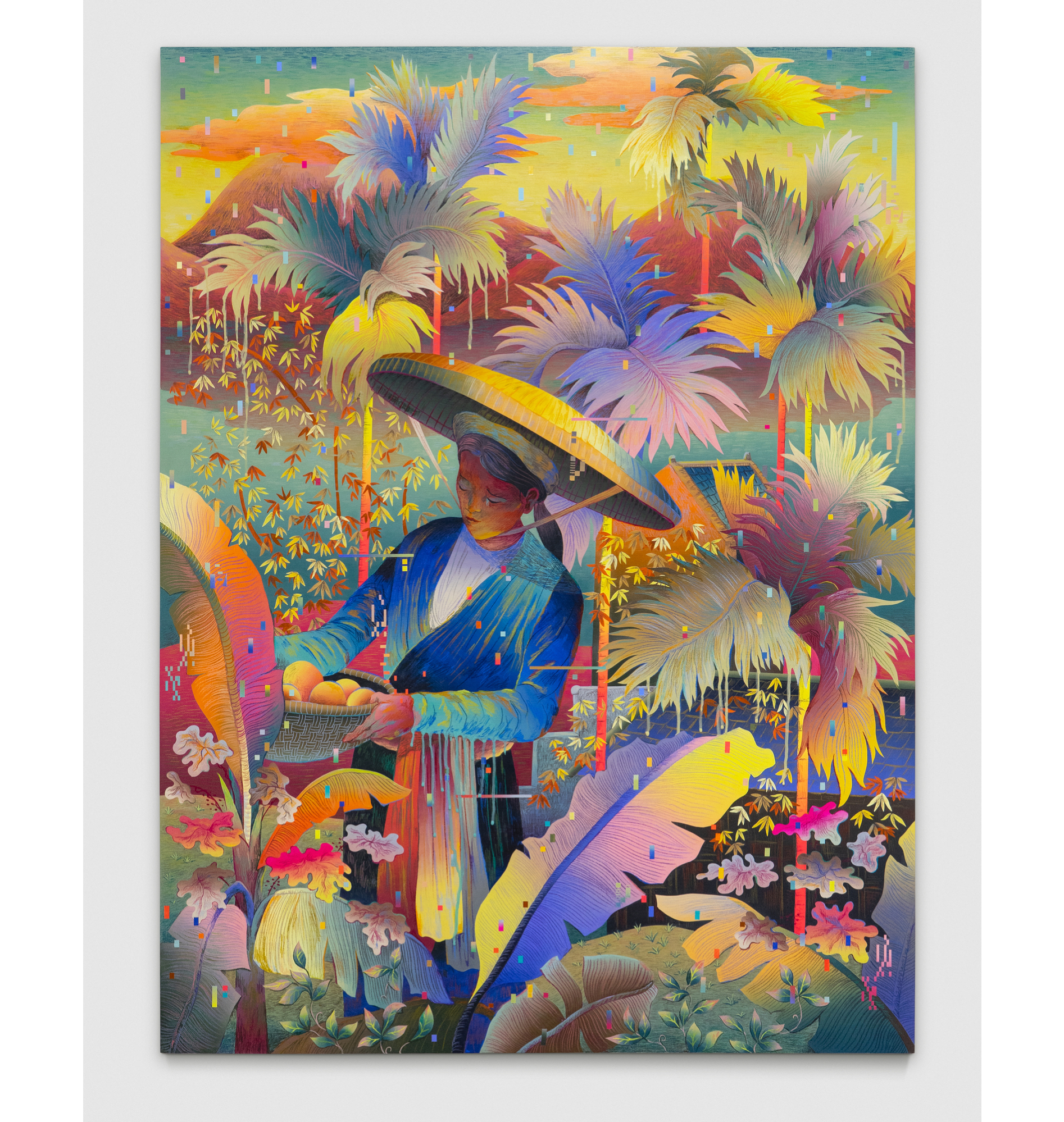

“The Vietnamese people under the two oppressions - one by the imperialists and one by the feudalists (Painter: Duy Nhắt).”

The difference? Vietnamese contemporary artists have been processing this colonial trauma through visual art for decades, creating sophisticated work that addresses cultural hybridity, memory, and identity. Korean students, meanwhile, often encounter their own colonial history primarily through textbooks and nationalist narratives that don't leave much room for nuance.

A reenactment of a colonial-era interrogation session in the Seodaemun Prison.

This parallel isn't just interesting—it's pedagogically powerful. These historical similarities create a ready-made framework that allows Korean students to access deep emotional and intellectual realizations about their own culture through Vietnam's parallel experience. It's not random cultural tourism where you're thrown into an unfamiliar context and expected to figure it out. Instead, the structural similarities between Korean and Vietnamese colonial histories provide a primer—a way in—that makes profound engagement possible even in just two weeks.

You recognize patterns in Vietnamese cultural responses because they echo Korean experiences your grandparents lived through. This recognition creates the emotional aperture for genuine artistic inspiration, not the forced creativity of typical study-abroad programs.

When Korean and Vietnamese Artists Ask the Same Question

Consider artists working in different countries but grappling with identical tensions: How do you use traditional forms to make sense of modern identity?

Kim Hyeonjeong paints women in hanbok eating McDonald's, playing pool, rock climbing—everyday modern behaviors rendered in traditional Korean painting (동양화) techniques using hanji paper collage. Her work satirizes contemporary Korean women's lives while honoring the formal elegance of traditional Korean aesthetics. The hanbok becomes translucent in her paintings, revealing the body beneath, suggesting that traditional forms can't quite contain modern realities.

Chiron Duong (born 1996) creates his "Portraits of Ao Dai" photography series—a 365-day project documenting Vietnamese women in ao dai across multiple contexts: personal memory, Vietnamese poetry and painting, love for homeland, folklore activities, wartime experiences, aspirations for peace. His work explores how traditional Vietnamese dress "contains a long history, cultural traditions, aesthetic conceptions, national consciousness, and spirit of the Vietnamese people" while existing in thoroughly contemporary contexts.

Xuân-Lam Nguyễn, a Fulbright scholar and RISD MFA candidate, describes his artistic approach as "a combination of an archeologist and a DJ"—excavating Vietnamese folk painting traditions and colonial-era photographs, then remixing them into contemporary installations. His work asks: "How do you preserve Vietnamese identity within an aesthetic framework shaped by the West?" Whether creating public installations inspired by Hàng Trống folk paintings or reinterpreting colonial photographs, Nguyễn navigates the same tension between tradition and modernity that defines contemporary Korean art.

These artists all use their nation's traditional aesthetics as a canvas for exploring modern identity. They navigate the painful question of what happens to cultural identity under pressure—whether from colonialism, globalization, or simply the tension between tradition and contemporary life. They refuse to let traditional forms become museum pieces, instead insisting that traditional aesthetics can contain the full complexity of modern experience.

This is why the Vietnam residency works: you'll encounter Vietnamese artists wrestling with the exact questions Korean artists face. Chiron Duong's photography and Xuân-Lam Nguyễn's folk art remixes speak directly to Kim Hyeonjeong's hanbok paintings. The formal similarities make the cultural differences visible, and vice versa.

When you see contemporary Vietnamese artists creating work about traditional dress and modernity, you'll recognize the pattern instantly—because you've seen Korean artists do the same thing. That recognition becomes the foundation for understanding both cultures more deeply.

Why Our Partnership Model Matters

The partnership with Chau & Co. Gallery isn't a transactional arrangement where we rent space and treat Vietnamese artists as service providers. It's a genuine collaboration built on mutual respect and shared intellectual goals.

What makes this different:

We're Not Extracting—We're Collaborating

Vietnamese artists aren't "helping" Korean students as a charitable service. They're engaging as professional equals who have insights and techniques that Korean students lack. Your Vietnamese mentor isn't there to make you feel good about yourself; they're there to push your work to professional standards and share perspectives you couldn't access in Korea.

We're Not "Giving Back"—We're Learning

This program doesn't pretend that Korean students are bringing something valuable to Vietnam that Vietnam lacks. We're explicit: Korean students are coming to learn from Vietnamese artists and cultural producers who have been doing sophisticated work on colonial memory, hybrid identity, and cultural resistance for decades. The transaction is primarily educational—Korean students receive access to Vietnamese intellectual and artistic traditions that are more developed than Korea's in certain domains.

We're Not Saving Anyone—We're Building Networks

The goal isn't to "help Vietnam" (which would be patronizing neo-colonial nonsense). The goal is to create peer relationships between emerging Korean and Vietnamese artists that will last beyond the program. These aren't charity relationships; they're professional networks built on genuine artistic exchange.

We Pay Appropriately

Vietnamese artists receive professional rates for their mentorship, not token honoraria. Gallery space is compensated fairly. This isn't exploitation masked as cultural exchange—it's a business relationship built on mutual benefit where Vietnamese cultural workers are paid what their expertise is worth.

Why Vietnam Instead of Somewhere Else?

Sure, Korean money goes farther in Vietnam than in Japan or the US. But that's not the only reason we're there.

We're in Vietnam because Vietnamese artists have spent decades creating sophisticated work about post-colonial identity, cultural hybridity, and national memory — exactly the themes Korean students need to understand about their own culture but often can't access from inside Korea's nationalist frameworks.

We're in Vietnam because the parallel colonial histories create immediate emotional and intellectual recognition that makes deep engagement possible even in short programs.

We're in Vietnam because Hanoi has a thriving contemporary art scene that operates with creative freedom, allowing for critical artistic work that addresses difficult historical questions.

We're in Vietnam because Vietnamese cultural producers are doing intellectual work that Korean students need exposure to—not because Vietnam is cheap or conveniently located or offers good photo opportunities.

If you're looking for a program where you go to Vietnam to feel good about helping people less fortunate than yourself, this isn't it. If you're looking for a program where Vietnam is just a cheaper, more exotic backdrop for activities you could do anywhere, this isn't it. But if you're ready to engage with Vietnam as an intellectual and artistic equal—as a place that has things to teach you that you can't learn anywhere else—then keep reading.

Not Art Camp. Not Study Abroad Tourism. Actual Artist Residency.

Let's be clear about what this program is not: it's not an Instagram-ready cultural tourism package where you make some crafts, take photos at temples, and call it "international experience."

This is a legitimate artist residency program that happens to be designed for advanced high school students who are ready for graduate-level cultural research. You'll be working in a professional contemporary art gallery in Hanoi's emerging art district. You'll have one-on-one mentorship with practicing Vietnamese artists. You'll create installations, paintings, sculptures, or multimedia work that gets exhibited in actual gallery space.

Here's what almost no high school student has on their college application: legitimate gallery exhibition experience. Not a school art show. Not a student competition. An actual exhibition in a professional contemporary art gallery where real collectors, critics, and artists engage with your work. The partnership with Chau & Co. Gallery isn't a convenience—it's the entire point. This credential is nearly impossible to obtain as a teenager unless you're already connected to the professional art world or attending elite art academies.

Gallery director Hoang Minh Chau specifically focuses on emerging artists and international cultural exchange—her mission is "making art seen" and integrating foreign artists into Vietnam's contemporary art scene. This isn't a student program grafted onto a gallery; it's a genuine residency adapted for the unique needs of Korean students exploring cultural parallels.

The Pedagogical Framework: How Historical Parallels Enable Deep Creative Work

Most international programs fail because they throw students into unfamiliar contexts without frameworks for making meaning. You visit temples, try local food, maybe volunteer somewhere, and come home with photos but no real insight.

This program works differently because the Korea-Vietnam colonial parallel provides structure without being prescriptive. Think of it as a primer that unlocks genuine artistic exploration:

The Framework Provides:

Emotional Access Points: Vietnamese experiences with French colonialism mirror Korean experiences with Japanese colonialism closely enough that you can feel your way into understanding through empathy rather than abstract study

Comparative Methodology: Having two parallel cases lets you see what's universal about colonial trauma versus what's culturally specific, which is exactly the kind of sophisticated analysis universities want

Authentic Creative Inspiration: When you recognize your grandmother's stories in a Vietnamese artist's installation about memory and displacement, that recognition becomes raw material for your own creative work—not forced, but organic

What It Doesn't Provide:

Predetermined conclusions about what you should think or feel

Packaged interpretations that reduce complex histories to simple narratives

Step-by-step instructions for what art you should make

The colonial parallel is a doorway, not a box. It gives you enough structure to engage deeply in just two weeks, but enough openness that your creative response will be genuinely yours—shaped by your own family history, your own emotional responses, your own artistic sensibilities.

This is why students consistently produce work during this residency that's far more sophisticated and personally meaningful than anything they've created in traditional art classes. The framework enables depth without constraining creativity.

Four Ways to Engage (Choose Your Track)

Track 1: Cultural Ethnography & Trend Research

For students interested in how culture actually moves between countries. You'll conduct fieldwork on Korean cultural influence in Vietnam (Korea-style cafés, fashion adoption, consumer behavior), learning the professional research methods Dr. Hurt uses when consulting for Google, Meta, and Pinterest. This combines anthropology, marketing strategy, and visual culture analysis—preparing you for careers in cultural consulting or international business.

Track 2: Documentary Photography

Master visual storytelling through all documentary contexts—street photography, environmental portraits, still life, interior documentation. Study the masters (Cartier-Bresson, Lange, Fan Ho, Salgado) while building your own photo essay about contemporary Vietnamese life. Perfect for students who understand that photography is thinking, not just clicking.

Track 3: Comparative Colonial Histories Through Art

The most academically rigorous track. Research parallel colonial experiences in Vietnamese and Korean archives, then create installations comparing how both cultures process colonial trauma. Work with Vietnamese artists on projects exploring memory, hybrid identity, and post-colonial aesthetics. This track includes graduate-level mentorship and potential for academic publication.

Track 4: Contemporary Vietnamese Identity

Collaborate directly with emerging Vietnamese artists on installations and multimedia projects exploring modern cultural identity. Less about colonial history, more about contemporary cultural production—how Vietnamese artists navigate tradition, globalization, and local community engagement.

What Two Weeks Actually Looks Like

Week 1: Immersion & Research

Days 1-2: Orientation at Chau & Co. Gallery, meet your Vietnamese artist mentor, select your project focus

Days 3-7: Intensive fieldwork—visit museums, archives, artist studios; conduct interviews; photograph neighborhoods; gather visual research; participate in gallery events and artist talks

Week 2: Creation & Exhibition

Days 8-12: Full-time studio work in gallery space with mentor guidance; daily critiques and project development

Days 13-14: Exhibition preparation, final presentations to Hanoi art community, portfolio compilation

Students will stay in be in guesthouses or vetted homestays — not fancy hotels off in tourist zones, because they’'ll need to actually live in local areas to understand the cultural context. We'll eat at local restaurants where real people gather. We'll attend openings and performances in Hanoi's contemporary art scene.

This is immersive to the point of being uncomfortable, which is exactly the point.

Why This Matters for Your Future

For College Applications:

Universities don't want another student who spent two weeks "volunteering" at an orphanage or went on a cultural tour. They want documented creative achievement in professional contexts. Gallery exhibition history. Mentorship from practicing artists. Academic research that contributes to ongoing scholarly conversations.

But here's what admissions officers almost never see: a high school student with legitimate gallery exhibition credentials. Most teenage artists show work in school hallways or student competitions. Having your work exhibited in a professional contemporary art gallery alongside practicing artists—with your name in exhibition materials, with real critical engagement from the local art community—puts you in a category that virtually no other applicants can claim. This isn't resume padding. This is a professional artistic credential that most people don't achieve until graduate school.

For Understanding Korean Identity:

You can't really see your own culture clearly when you're standing inside it. Vietnam gives you the critical distance—similar enough to recognize patterns, different enough to see what's specifically Korean rather than universally Asian. The colonial parallels create emotional resonance that textbooks never achieve. Students consistently report that the residency changed how they understand their own family histories and Korean cultural narratives—not because someone lectured them, but because they felt the recognition themselves while working alongside Vietnamese artists processing parallel trauma.

For Building International Networks:

You'll work alongside Vietnamese artists who are building careers in Asia's contemporary art market. These relationships continue after the program through exhibitions, collaborations, and professional connections that span multiple countries.

The Practical Details

When: January 2026 (2 weeks intensive)

Where: Chau & Co. Gallery, Hanoi, Vietnam

Group Size: 5-10 students (small cohorts for intensive mentorship)

Cost: $6,100-7,200 all-inclusive (program fees, accommodation, mentorship, materials, gallery access)

Prerequisites: None — program designed to develop students from basic interest to professional capability

Who Should Apply

This program works for students who:

Want to create meaningful art, not just pad their résumé

Can handle ambiguity and cultural discomfort

Are genuinely curious about how colonialism shapes contemporary culture

Prefer depth over breadth—intensive engagement rather than superficial tourism

Want to understand Korea by temporarily leaving it

Are ready to produce work that emerges from real emotional and intellectual engagement rather than following predetermined formulas

Can accept that Vietnamese artists and cultural producers have valuable knowledge that Korean students lack

This doesn't work for students who:

Need constant structure and can't handle independent work

Are looking for an easy international experience to list on applications

Want to "help" Vietnam or feel good about charitable service

Expect to be treated as special because they're paying customers

Can't handle critique from Vietnamese mentors who will push their work hard

The Uncomfortable Truth About Cultural Understanding

Here's what we've learned after years of running international programs: you can't understand your own culture through tourism. You can't understand colonial history through textbooks. You can't develop sophisticated cultural analysis through short-term volunteer work that positions you as the helper and local people as the helped.

But you can understand Korean identity by watching Vietnamese artists process parallel colonial trauma through contemporary art. You can develop visual literacy by documenting Hanoi's streets for two weeks straight. You can build genuine cross-cultural competence by collaborating on installations that neither Korean nor Vietnamese artists could create alone.

The Korea-Vietnam parallel isn't a gimmick — it's a pedagogical foundation that transforms what's possible in a short-term program. The historical similarities don't constrain your creativity; they provide the framework that makes deep creative work achievable even in two weeks. You're not starting from zero trying to understand an entirely foreign context. You're starting from recognition, from parallel experience, from shared historical wounds—and that foundation enables you to create work that's both personally meaningful and intellectually sophisticated.

The Vietnam Winter Art Residency succeeds because it refuses the easy path while providing the framework that makes the difficult path navigable. It puts students in professional artistic contexts where they're expected to produce real work. It demands engagement with uncomfortable historical parallels. It requires creative risk-taking in unfamiliar cultural environments. But it gives you the tools—through the colonial parallel, through Vietnamese artist mentorship, through professional gallery context—to actually succeed at this demanding work.

Universities recognize this kind of achievement because it's rare. It demonstrates genuine intellectual curiosity, creative capability, and cross-cultural sophistication—the exact qualities selective institutions claim to want but rarely find in applicant pools dominated by resume-padding and strategic volunteering.

Ready to Create Something That Matters?

The next Vietnam Winter Art Residency runs in Winter 2026. Applications open in late 2025.

For students who've outgrown surface-level international experiences and want to engage with Asian cultural production at a professional level, this program offers something genuinely different: the chance to develop as an artist while understanding your own culture through someone else's parallel story, and to earn professional credentials—gallery exhibition history—that almost no other high school student possesses.

Vietnam and Korea share colonial wounds. Through contemporary art practice in a professional gallery setting, you'll explore how both cultures are still healing—and in the process, you might create work that contributes to that healing while building a portfolio that stands out in any application pool.

But only if you're willing to engage with Vietnam as an equal, as a partner with valuable knowledge to share, rather than as a backdrop for your personal development journey.

Contact KARSI for application details and program information.

The Vietnam Winter Art Residency is a collaboration between KARSI (Korean Advanced Research & Studies Institute) and Chau & Co. Gallery, combining Dr. Michael Hurt's expertise in Korean-Vietnamese cultural flows with Hoang Minh Chau's commitment to emerging artist development and international cultural exchange.

AI Usage Acknowledgment

This article was developed through collaboration between Dr. Michael Hurt and Claude (Anthropic). AI assistance was used for research synthesis, structural organization, and drafting. All substantive content, pedagogical frameworks, program details, and critical arguments reflect Dr. Hurt's expertise in Korean-Vietnamese cultural flows, visual sociology methodology, and educational program design developed over 17+ years of research and practice. Background research on contemporary Vietnamese and Korean artists was conducted using web search tools, with all factual claims verified against primary sources. Final editorial decisions, program philosophy, and strategic positioning remain under human direction.