Your AI Can't Do Fieldwork: Why Real Research Beats FakeRY Every Time

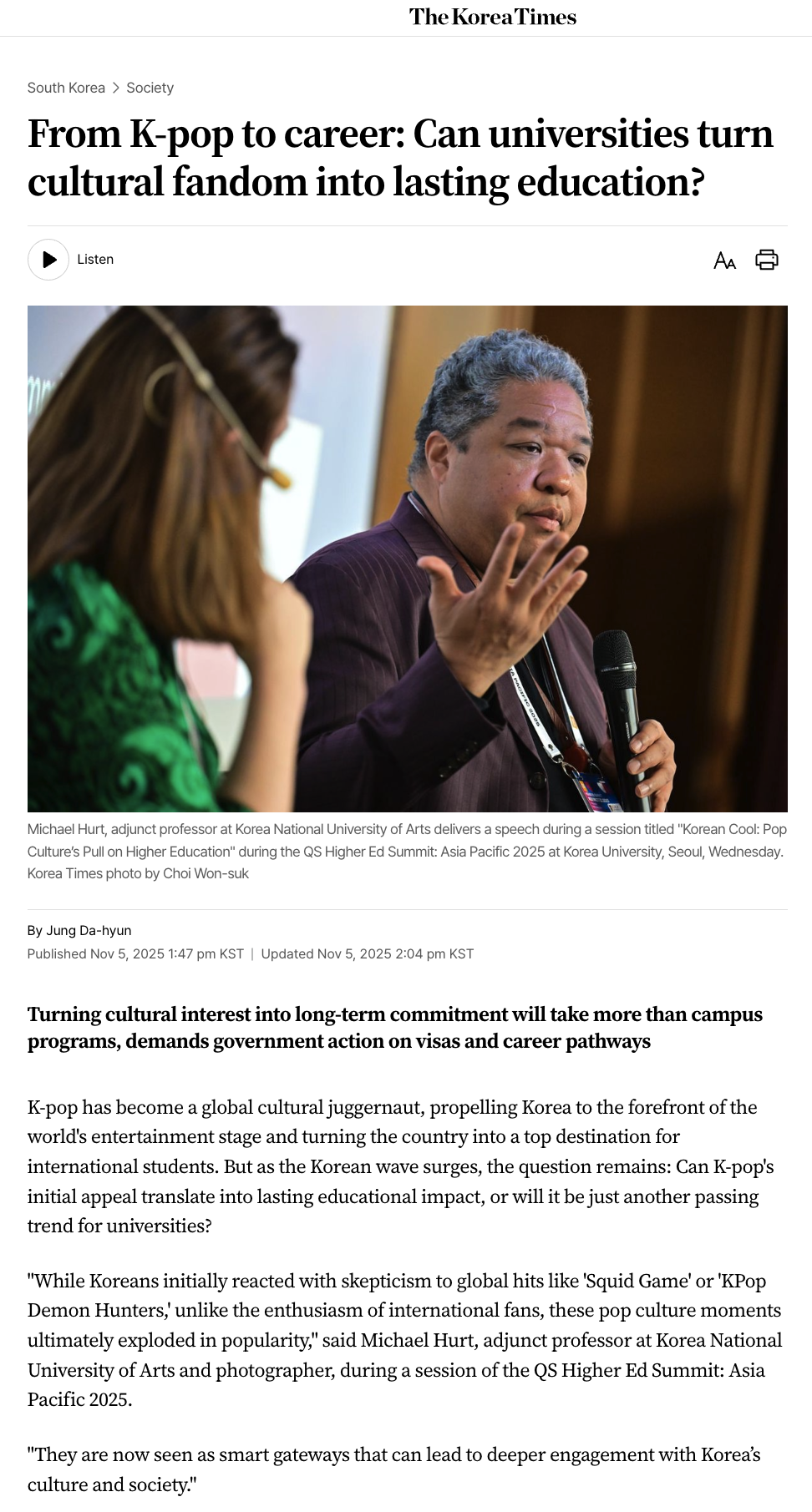

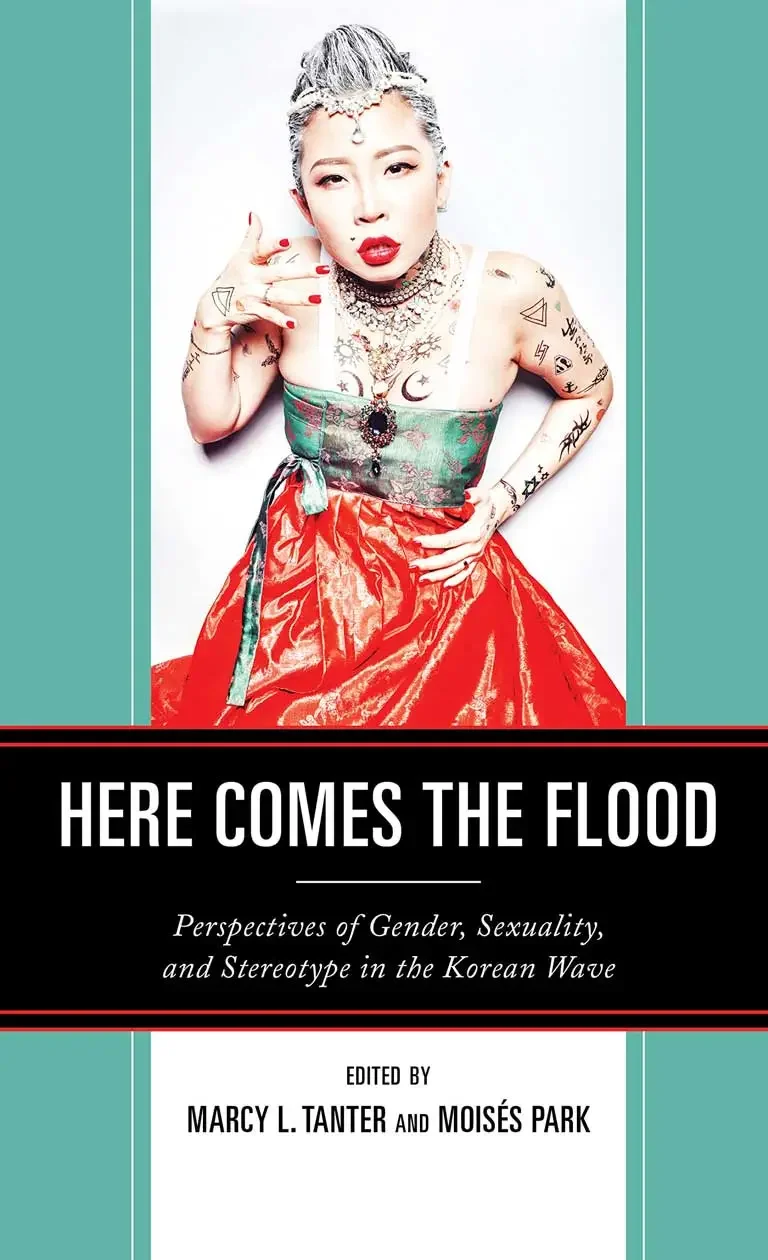

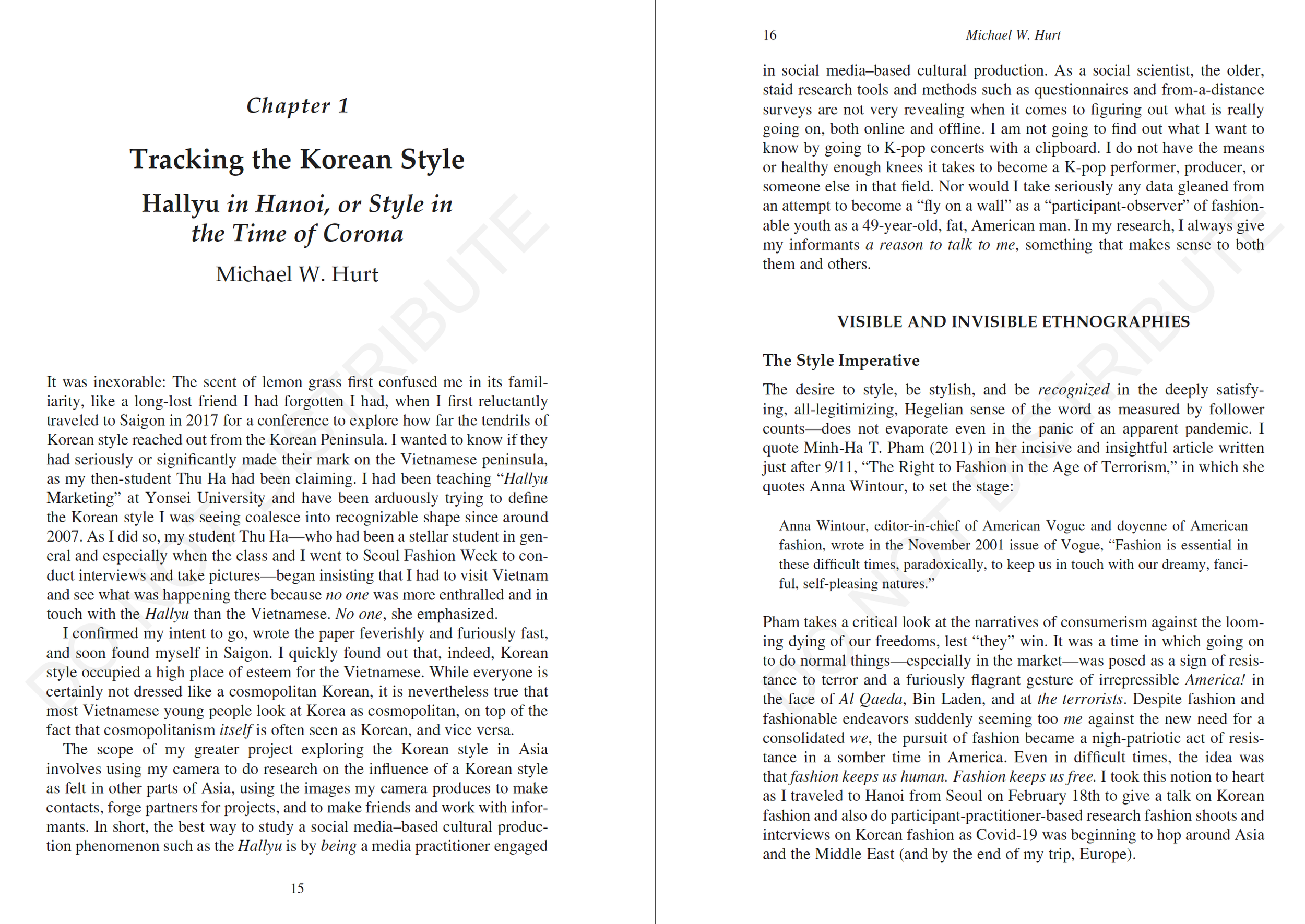

From the “Hanbok in Hanoi” project in February/March 2020, in which a Vietnamese model wore a hanbok to help spatially explore putatively Korean spaces in Hanoi, which resulted in Dr. Hurt’s leadoff book chapter “Tracking the Korean Style: Hallyu in Hanoi, or Style in the Time of Corona“ and the cover image for the book “Here Comes the Flood: Perspectives of Gender, Sexuality, and Stereotype in the Korean Wave.” We do real research.

Your admissions officer knows you used ChatGPT.

They know because everyone used ChatGPT. They know because every personal statement now has that slightly-too-polished quality, that generic inspirational arc, that suspicious absence of actual voice. They know because they've read five hundred essays this week and they all sound like they came from the same algorithmic template.

And here's the brutal truth: even if you didn't use AI, even if your story is genuinely yours, even if that inspirational arc actually happened to you — it doesn't matter. Your authentic experience now reads as suspicious because everyone else's fake experience looks exactly the same. The field is dominated by algorithmic fakery, and honest students are also drowning in it.

What can you put in front of an admissions committee that proves actual intellectual capability? What experiences can't be prompt-engineered into existence?

The answer is simpler than you think: Real research. Actual fieldwork. Scholarly activity that required you to be physically present, intellectually engaged, and genuinely contributing to knowledge production.

You know what ChatGPT can't do? Conduct ethnographic interviews in Hanoi. Create gallery installations with Vietnamese artists. Document cultural transmission patterns in Butuan City, doing research on a university-back project. Building relationships with research subjects who don't speak English. While navigating the methodological challenges of comparative cultural analysis in real time.

Your AI can write about cultural understanding. It cannot generate the experience of cultural understanding. And admissions officers — the good ones, at the universities that matter — know the difference.

The Difference Between Tour Guides and Professors (And Why It Matters)

This isn’t a tour. Dr Hurt, director of KARSI and an experienced ethnographic researcher, is conducting actual fieldwork and scouting for a place to shoot according to his photo-sartorial elicitation protocols in Hanoi’s Old Quarter.

Let's be honest about what most "cultural immersion" programs actually are: tourism with academic cosplay. Nice people who mean well, taking students to interesting places, calling it educational programming. Educational coordinators. Program facilitators. Cultural liaisons.

We brought a different set of tools.

Actual university professors. A professor teaching in the Syracuse University Asia Program and at the Korea National University of Arts with a Berkeley PhD. A Harvard PhD scholar with 30+ years field research and government cultural designations. These aren't tour guides managing logistics. These are working academics teaching at universities with research agendas, publication records, and ongoing field projects who need research assistants.

The difference matters. When you join a KARSI program in Vietnam or the Philippines, you're not joining an educational tour. You're joining a research expedition led by professors who teach at actual universities. Your instructors aren't facilitating your learning experience—they're actual university professors conducting scholarly research and training you in methodology because they need competent help in the field.

This is what "research experience" actually means. Not a simulation. Not an "introduction to research methods" course. Actual participation in ongoing scholarly projects led by university professors—projects that will result in academic publications, conference presentations, and advancement of knowledge in the field. You're part of the research team. That's what goes in your portfolio.

You're not paying for credentials. You're earning them.

Think about what that means for your portfolio. Not "I participated in a cultural exchange program." But "I served as research assistant on ethnographic research tracking Korean cultural transmission in Southeast Asia under the direction of a university professor with a UC Berkeley PhD." Not "I learned about Vietnamese culture." But "I contributed to ongoing research on hip-hop as cultural vernacular in Hanoi's youth culture."

It's not even close to a fair fight. Everyone else brought tour guides. We brought professors who teach at universities.

The Cookie-Cutter Portfolio (And Why Admissions Officers Spot It Instantly)

Korean families already know this truth, even if they don't always say it out loud: most overseas educational programs are cookie-cutter operations designed for scale, not substance.

The volunteer trip where thirty students descend on a village for five days of "service learning." The leadership camp where everyone receives the same certificate. The cultural immersion program that's fundamentally tourism with an educational veneer — museums, historical sites, maybe some language classes, call it cross-cultural competency.

Admissions officers see these portfolios constantly. They know the patterns. They know what commodified educational experiences look like. They know when students are buying credentials versus earning them.

Here's what they're looking for instead: evidence of genuine intellectual development. Proof that a student can handle ambiguity, navigate complexity, produce original work. Demonstration that someone has done something difficult that required actual growth.

You cannot purchase that. You cannot package it as a service. You cannot deliver it through standardized programming designed for efficient processing of large student cohorts.

You can only create it through authentic intellectual work with serious scholars who refuse to compromise on rigor.

The Korean Advantage Nobody's Using

Director of KARSI, Dr. Michael Hurt has been talking about the need to make on-the-ground sense of Korean popular culture for decades, and major organizations such as universities are finally starting to take the surge in Korea-related interest seriously.

Here's the part that should be obvious but somehow isn't: Korean students are sitting at the epicenter of the most studied cultural phenomenon of the 21st century. Korea is the hottest cultural market in the world right now. The Korean Wave — Hallyu — is the subject of academic conferences, university programs, and research institutes across every continent.

Universities globally are desperate to understand Korean cultural transmission. Scholars from the US, Europe, Southeast Asia, Latin America are flying to Seoul, learning Korean, trying to access the cultural industry networks and social contexts that Korean students navigate daily.

We know this because they're showing up to our programs. This past summer, we had a Finnish student through our Erasmus+ partnership specifically come to Korea to study with KARSI. This winter, Curtin University is bringing Australian students to Seoul for Korean studies through the New Colombo Plan—and they're sending interns to work with KARSI because our research is good enough to meet their standards. They're flying across the world, learning Korean as a second language, studying Hallyu flows because they recognize this is where cutting-edge cultural research is happening right now.

And what are Korean students doing with this insider advantage? Volunteer tourism in Cambodia. Generic leadership camps. The same cookie-cutter programming as everyone else.

This is strategic malpractice.

Korean students should own the research space on Korean cultural flows. They have native cultural competency. They understand the nuances of Korean aesthetic production that foreign scholars spend years trying to grasp. They can access networks and contexts that outsiders cannot. They are insiders to the most globally significant cultural phenomenon of their generation.

KARSI exists specifically to help Korean students leverage this advantage. Our research programs track Hallyu flows throughout Asia—Korea to Vietnam, Korea to Philippines, Korea to Indonesia. This is frontier scholarship. We've signed an MOU with a major Philippine university specifically because they recognize the significance of this research and want Korean students documenting how Korean cultural transmission operates in their region.

And because Korea is the hottest cultural market globally right now, we're building an international research network. Our partnerships with Australia's New Colombo Plan (bringing Curtin University students) and Finland's Erasmus+ programs mean Korean students work alongside international peers who specifically chose Korea as their research focus. These are future academics, cultural industry professionals, and policy makers who will be working on Korea-related projects throughout their careers. The connections Korean students build in KARSI programs aren't just educational—they're professional networks in a field where Korea is the center.

Think about what that means: A Philippine university is formally partnering with us because Korean students have unique insider knowledge that matters to their academic community. Curtin University's New Colombo Plan program trusts KARSI enough to send us interns from their Seoul cohort. Finnish students are choosing Korea as their Erasmus+ destination. International institutions recognize what Korean students are somehow missing: you have unprecedented access to the most significant cultural phenomenon of the 21st century.

That's your competitive advantage. That's what you should be building your portfolio around. That's the research network you should be joining.

Not generic volunteer work that could be done by any student from any country. But research that only Korean students can do at this level—documenting and analyzing cultural flows from a position of insider expertise that foreign scholars cannot replicate.

You're sitting on a gold mine. The question is whether you're going to claim it.

The KARSI Difference: Authenticity Nobody Else Can Offer

The book in which Dr. Hurt’s chapter is not only featured as Chapter 1, but which used one of his key photo-sartorial elicitation images as the cover.

Images, when examined in terms of the data they directly present — and not merely as illustrations of written text — are the main character in ethnographic work.

This is why our Vietnam and Philippines programs exist — not just as destinations, but as strategic research sites where Korean students can leverage their cultural insider positions.

Not because we thought "Korea-interested students might enjoy Southeast Asia." But because Vietnam and the Philippines are right now the live laboratories where Korean cultural transmission is happening in real time. And Korean students—with their native understanding of Korean cultural production—are uniquely positioned to document these flows. These are not historical case studies. This is contemporary cultural flow that hasn't been adequately documented, hasn't been properly theorized, and represents genuine frontier territory in Korean studies scholarship.

When you're in Hanoi conducting interviews about K-pop influence, you're not studying something that's already been settled by previous scholarship. You're generating primary data on Korean cultural flows from an insider position that foreign researchers cannot access. When you're working with artists at Chau & Co. Gallery, you're not replicating existing work—you're creating original installations that demonstrate Korean aesthetic understanding. When you're in Butuan City examining how Korean aesthetic practices operate in a Catholic-Filipino context through our MOU partnership with Caraga State University, you're part of the first systematic investigation of these questions—working alongside university professors who know how to turn field observations into publishable research.

This is ground-floor research. The kind that defines fields for decades. Not generic undergraduate papers rehashing settled debates for the Journal of Student Research. This is real frontier scholarship that professors are conducting—and you're getting to be part of the process. Research assistant experience on actual academic projects. The kind of portfolio material that shows you worked alongside scholars doing original research that matters to the field, not just completed a class assignment.

Your instructors aren't teaching curriculum they downloaded from somewhere. They're building the curriculum from their active research programs—because they're actual university professors doing real scholarship. The difference between learning about ethnographic methodology and actually doing ethnographic fieldwork with a college professor who's publishing in the area? That's the difference between tourism and research. Between credentials you bought and credentials you earned.

And here's the critical advantage in the age of AI disruption: this work cannot be faked. You can't ChatGPT your way through field interviews. You can't prompt-engineer a gallery installation. You can't algorithmically generate the insight that comes from genuine cultural immersion combined with serious methodological training.

The portfolio material you build from KARSI programs is irreducibly authentic. It proves intellectual capability in ways that resist commodification. It demonstrates research skills that universities actually value. It shows admissions committees something they desperately want to see: evidence that you've participated in real scholarly processes, not just consumed educational content.

Dr. Hurt and his assistant preparing for his lecture “The case of Korean success in the realm of the street fashion field” as an invited presenter to the “From Possibilities to Vision and Action: Preparing Viet Nam for Its Next Phase of Growth” conference in Danang in 2018.

Choose Accordingly

The question isn't whether your student needs distinctive portfolio material. In the current admissions climate, everyone needs distinctive portfolio material. The question is whether you're going to pursue authenticity or settle for credentialing theater.

Educational tourism dressed up as cultural immersion? ChatGPT essays polished to algorithmic perfection? Volunteer experiences that look suspiciously identical to every other applicant's volunteer experiences? These strategies worked when universities couldn't tell the difference. They don't work anymore.

What works now: Irreducibly authentic experiences. Real research with university professors. Actual scholars teaching at universities providing genuine research mentorship.

KARSI offers that. Vietnam and the Philippines offer that. University professors with PhDs from UC Berkeley and Harvard offering genuine research mentorship offer that.

Nobody else in Korea has these assets. Nobody else is offering actual university-level research training with real professors teaching at universities in the frontier territories of Korean studies scholarship. Nobody else brings this combination of top-tier PhD credentials, active teaching positions at universities, regional expertise, and commitment to authentic intellectual development.

And nobody else is helping Korean students leverage their unique insider advantage in the most globally significant cultural phenomenon of their generation.

The programs exist. The research sites are ready. The university professors are there.

The only question is whether you want your student learning about research or actually participating in research. Whether you want credentials they bought or credentials they earned. Whether you want a portfolio that looks like everyone else's or evidence of genuine intellectual engagement that can't be faked. Whether you're going to leverage the Korean advantage or waste it on generic programming.

We know which side of that choice we're on.

The question is: Do you?

KARSI (Korean Advanced Research & Studies Institute) offers intensive research programs in Vietnam and the Philippines for students ready to engage Korea as serious research object. Programs combine rigorous methodology training with hands-on fieldwork under university professor supervision. Dr. Hurt and his particular research tracks/courses through Seoul, Vietnam, Indonesia, and the Phillipines are just one example of the kind of diverse research experiences KARSI has to offer for intrepid and enterprising young students.

Learn more at www.karsi.org

AI Usage Statement: This article was drafted using Claude AI as a writing assistant under the direction and editorial supervision of the KARSI director. All research claims, program descriptions, and institutional partnerships reflect actual KARSI operations. The content has been reviewed and approved for accuracy and alignment with institutional values. KARSI adheres to AI usage and disclosure protocols currently being developed at Stanford University, MIT, and the University of California system. These protocols require: (1) explicit documentation of AI tool usage in research and writing; (2) clear specification of which tasks were performed by AI versus human direction and oversight; and (3) unambiguous attribution of intellectual responsibility and authorship to human scholars. This statement balances transparency with accessibility, reflecting KARSI's commitment to clear disclosure practices while maintaining rigorous standards for human expertise and editorial control.