Denationalizing Korean Studies: Against the Soft Power Paradigm

Abstract

For two decades, scholarship on Korean popular culture and its global circulation has been organized by the soft power paradigm—a framework borrowed from American foreign policy discourse that treats cultural influence as national achievement and receiving contexts as targets to be captured. This article argues that the soft power framework is theoretically exhausted and ethically compromised. Through close analysis of the field's dominant vocabulary—"penetration," "conquest," "capture," "cultural weapon"—I demonstrate that Korean studies has adopted the language of sexual violence and military assault to describe cultural exchange, naturalizing the idea that influence means domination. Drawing on fieldwork in Vietnam that revealed processes invisible to origin-point analysis, we propose an alternative: Korea as Signifier. This framework refuses the nation-state as organizing unit, treats "Korea" as a floating signifier rather than a stable referent, and recognizes semiotic slippage—when "Korea" operates independently of Korean content—as the actual mechanism of cultural transmission rather than its failure. The field must choose between continued complicity in cultural imperialism dressed up as scholarship, or the harder work of asking what the signifier "Korea" actually does in the world.

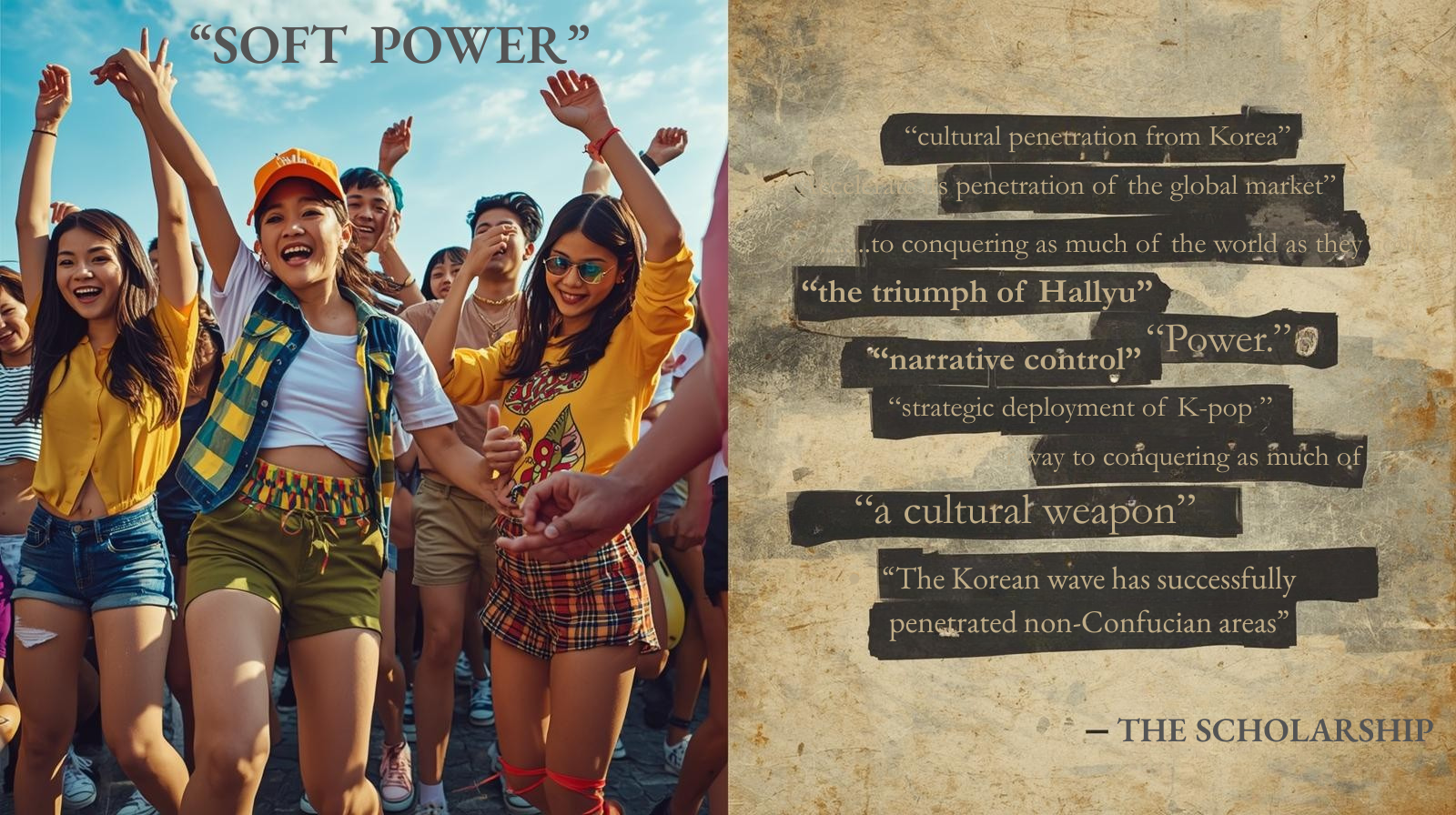

I. The Vocabulary Speaks for Itself

Consider the following passages from respected academic publications on the Korean Wave:

"a somewhat intimidating cultural penetration from Korea"

"The Korean wave has successfully penetrated non-Confucian areas like Malaysia, Egypt, Latin America, central Asia, and Russia"

"Korea's pop culture happened to capture the enthusiasm of Chinese youngsters"

"accelerate its penetration of the global market"

"on their way to conquering as much of the world as they could get to"

"a cultural weapon to entice, attract, and influence international audiences"

"strategic deployment of K-pop groups, dramas, and digital content"

"the triumph of Hallyu"

"global powerhouse"

"narrative control"

These are not from Korean government press releases. They are from peer-reviewed journals, academic monographs published by major university presses, and articles in respected international communication scholarship. This is what passes for neutral description in Korean studies.

Read them again. Penetration. Capture. Conquest. Weapon. Triumph.

We are using the vocabulary of sexual violence and military assault to describe teenagers in Manila doing cover dances.

This article argues that this vocabulary is not accidental, not merely unfortunate word choice, but revelatory. The language tells us what the soft power framework actually thinks cultural exchange is: a form of warfare in which one nation dominates others, in which audiences are targets to be hit, markets are territories to be conquered, and success means penetration of foreign bodies.

The soft power paradigm has captured Korean studies scholarship on popular culture. It is time to name what we are looking at—and to propose an alternative.

II. Soft Power: Origins, Assumptions, Legitimation

A. An American Imperial Concept

The concept of "soft power" entered international relations discourse in the late 1980s through American foreign policy scholarship. It was designed to describe how the United States could achieve its geopolitical objectives through attraction rather than coercion—culture, values, and institutions rather than military force or economic pressure.

The framework was never innocent. It was built to serve American imperial interests by providing a gentler vocabulary for influence operations. As critical scholars have demonstrated, soft power "provides the conditions of possibility for the use of hard power"—it precedes and legitimizes military violence by establishing the moral authority of the dominant power. The concept of "representational force" reveals how soft power rhetoric can itself function as coercion, forcing audiences to identify with the "good" side or be labeled as other.

Soft power was designed to make American cultural hegemony look like natural attraction. It succeeded.

B. The Korean Adoption

Korean studies imported this framework wholesale when Hallyu became a global phenomenon. Suddenly, scholars had a ready-made apparatus for analyzing Korean cultural exports: Korea was projecting soft power, foreign audiences were receiving it, and success could be measured in market penetration, favorable attitudes, and national brand value.

The legitimating moment came when the originator of soft power theory himself co-authored a chapter applying the framework to Korea. This was not a neutral academic development. It was a 사대주의 (sadaejuui) moment—deference to a perceived greater intellectual power, in this case the White West's theoretical authority. A Korean-American scholar partnered with the American architect of soft power to certify that yes, this American foreign policy concept properly describes what Korea is doing.

Performance studies scholar Hyunjung Lee provides the theoretical framework for understanding why Korean studies was so eager for this certification. In her dissertation "Global Fetishism: Dynamics of Transnational Performances in Contemporary South Korea" (UT Austin, 2008) and subsequent book Performing the Nation in Global Korea (Palgrave Macmillan, 2015), Lee argues that in South Korea, "global" has become synonymous with glamorous cultural success to such a degree that it functions as its own rationale. Drawing on Marxist commodity fetishism, Lee demonstrates how the notion of the "global" has become so elevated that it can give meaning and worthiness to just about anything—simply because it promotes Korea or Korean culture in the global realm. The "global fetish" is a rationalizing framework in which being recognized globally becomes self-justifying, regardless of what that recognition actually means or costs.

This explains the soft power adoption perfectly. Korean studies embraced Nye's framework not because it was analytically superior—it forecloses more questions than it opens—but because it satisfied the global fetish. Western theoretical validation made Hallyu scholarship count in the global academic realm. The soft power framework, invented by an American foreign policy scholar to describe American influence operations, was gratefully adopted because it made Korean cultural success legible in Western academic terms. Finally, validation from the source. Finally, a seat at the table of global knowledge production.

The field accepted this certification gratefully. But what did adopting this framework actually mean?

C. The Framework's Assumptions

Soft power scholarship on Korea operates through a set of assumptions that were never examined:

Methodological nationalism: The nation-state is treated as the natural unit of analysis. Soft power is always national soft power—Korea's soft power, America's soft power. The framework cannot think outside the nation-state container. Cultural processes that cross, ignore, or destabilize national boundaries become illegible.

Unidirectional flow: Cultural influence flows from origin to destination. Korea projects; others receive. This positions receiving contexts as passive—targets of cultural export rather than active participants in meaning-making. The creative labor of people in Vietnam, Indonesia, the Philippines, or Latin America disappears into Korea's "success."

Success as domination: The proper measure of cultural significance is national benefit. Soft power asks: Is Korea winning? Is Korean influence expanding? Are favorable attitudes toward Korea increasing? It cannot ask whether Korean cultural influence might be a form of imperialism, what people in receiving contexts actually want, or how cultural elements transform as they travel.

The violent vocabulary is acceptable: Penetration, conquest, capture, domination—the framework treats this language as normal, even celebratory. Markets are penetrated. Audiences are captured. The world is conquered. These are presented as achievements.

III. The Vocabulary of Violence

A. Mapping the Language

The violent vocabulary of soft power scholarship is not occasional or incidental. It is systematic. A survey of the field's canonical texts reveals consistent patterns:

Penetration—the dominant metaphor. Markets are penetrated. Regions are penetrated. Audiences are penetrated.

"a somewhat intimidating cultural penetration from Korea"

"successfully penetrated non-Confucian areas like Malaysia, Egypt, Latin America"

"accelerate its penetration of the global market"

Capture—audiences do not choose; they are captured.

"Korea's pop culture happened to capture the enthusiasm of Chinese youngsters"

"captured by the dominating/penetrating power"

Conquest—cultural spread as military campaign.

"on their way to conquering as much of the world as they could get to"

"the triumph of Hallyu"

Weapon—culture instrumentalized for attack.

"a cultural weapon to entice, attract, and influence international audiences"

Strategic deployment—the language of military operations.

"strategic deployment of K-pop groups, dramas, and digital content"

"narrative control"

B. The Genealogy of Violence

This vocabulary is not accidental. It has a genealogy.

Herbert Schiller, the foundational theorist of cultural imperialism, wrote in 1976: "For penetration on a significant scale the media themselves must be captured by the dominating/penetrating power."

James Petras, analyzing cultural imperialism in 2000: "Cultural penetration is the extension of counter-insurgency warfare by non-military means."

The vocabulary reveals the conceptual structure. When scholars use this language without problematizing it, they are not being sloppy—they are faithfully reproducing what the soft power framework actually thinks cultural exchange is: a form of warfare in which one side wins and the other side is dominated.

C. The Sexual Violence Register

"Penetration" is not only military language. The term carries unavoidable connotations of sexual violation—the forced entry into a body that has not consented. When scholarship celebrates Korea's "penetration" of foreign markets, it figures receiving populations as bodies to be entered. This is not over-interpretation—it is what the word means.

That this language passes without comment in peer-reviewed scholarship tells us something about what the field has normalized. We would not accept an academic framework that described Korean cultural influence as "raping foreign markets." But "penetrating" them is fine. The euphemism does the work of making violence speakable.

IV. Epistemological Closure: What Soft Power Cannot See

A. The Framework's Analytical Limits

Soft power analysis can measure:

Market share

Streaming numbers

Survey data on favorable attitudes

Export statistics

Social media engagement metrics

Soft power analysis cannot see:

Transformation (what happens to cultural elements after arrival)

Local agency (what receiving populations do with cultural material)

Creative appropriation (new meanings, new uses, new productions)

Refusal and rejection (what doesn't travel, what gets ignored)

Semiotic slippage (when "Korea" operates independently of Korean content)

B. The One Question

The framework can only ask: Is Korea winning?

This forecloses every other question:

Is Korean cultural influence a form of imperialism?

What do people in receiving contexts want, independent of Korean intentions?

How do cultural elements transform in ways that have nothing to do with national origins?

What does the category "Korea" do in different contexts?

What do receiving-end perspectives reveal that origin-point analysis cannot see?

This is epistemological closure. The soft power framework is not a neutral analytical tool that happens to have limitations. It is a machine for producing a particular kind of knowledge—knowledge that serves Korean state interests—while making other kinds of knowledge impossible.

C. The Hard Power Connection

Critical scholarship has demonstrated that soft power is not the gentle alternative to coercion it claims to be. Research from the Swedish Defence University shows that soft power "provides the conditions of possibility for the use of hard power." The rhetoric of cultural attraction precedes and legitimizes violence. Soft power is "not innocent, but potentially dangerous."

The concept of "representational force" reveals how soft power rhetoric can itself function as coercion—forcing audiences to identify with the "attractive" power or be positioned as resistant, backward, other.

The soft/hard distinction is ideological, not descriptive. It makes domination look like attraction.

V. The Funding Problem

A. Who Pays for Soft Power Scholarship?

The soft power framework's dominance in Korean studies is not merely intellectual. It is institutional and financial.

The Korea Foundation, the Academy of Korean Studies (AKS), and the Korean Foundation for International Cultural Exchange (KOFICE) have invested heavily in scholarship that frames Hallyu as Korean national achievement. This is not conspiracy; it is rational behavior. These are Korean government-affiliated institutions. Their mission is to promote Korean interests. Scholarship demonstrating Korean soft power success serves that mission.

B. The Language of the Grants

Consider the language of a major AKS grant: the proposal explicitly states that "Korean studies are the foundation for boosting public diplomacy" and aims to "globalize Korean culture including the Korean Wave."

A Korea Foundation-funded policy report announces: "South Korea's soft power reached new heights" and recommends that "Seoul must use this rising political capital wisely to build lasting influence beyond its borders."

KOFICE positions Hallyu as Korea's "greatest soft power asset."

The analytical frame and the policy recommendation are indistinguishable. Scholarship becomes an instrument of Korean state interests.

C. The Structural Capture

This funding structure creates predictable incentive effects. Scholars who frame their work as demonstrating Korean soft power success are rewarded. Scholars who might ask critical questions—Is Korean cultural influence a form of imperialism? What do receiving populations actually want? How does Korean state support for cultural industries distort markets and cultural production?—find such questions unfundable.

The result is a field that has largely converged on a single paradigm not because that paradigm is analytically superior, but because it is financially rewarded. Korean studies scholarship on popular culture has become, to a significant degree, an intellectual apparatus for celebrating Korean cultural success.

This is not an accusation against individual scholars. Most are not aware that they have adopted a framework with these implications. The soft power paradigm has become common sense—the unremarkable background assumption that organizes research questions, analytical methods, and evaluative criteria.

But common sense is precisely what requires interrogation.

VI. The Hanoi Discovery: What Receiving-End Perspectives Reveal

A. The Research Context

In 2025, I conducted follow-up fieldwork in Hanoi to research I began in 2019 on Korean cultural influence in Vietnam. I expected to find Korean content being consumed, Korean products being purchased, Korean styles being adopted. I expected to document penetration.

B. The Finding That Broke the Framework

What I found instead: spaces that read as Korean without using Korean content. Young Vietnamese producing "Korean-ness" for their own purposes. The category "Korean" operating as an aesthetic toolkit—a floating signifier—detached from anything Korea had actually exported.

Cafes styled themselves as "Korean" while serving Vietnamese coffee in spaces decorated with global design elements. Fashion choices were described as "Korean style" despite having no connection to Korean brands or Korean fashion media. "Korean" had become a grammar—a way of organizing aspirational urban modernity that people deployed for local purposes having nothing to do with Korean intentions.

None of this registers in soft power analysis. There was no Korean content being "projected." No market being "captured." No audience passively "receiving" Korean culture. Instead, there was active production—people using the signifier "Korea" to do things, make meanings, construct identities, for reasons entirely their own.

C. The Soft Power Framework's Blind Spot

Soft power analysts positioned in Seoul or Western academic centers could not have discovered this. The framework they use can only ask "how did Korean culture spread?"—and when the answer is "it didn't, but the category Korea is being deployed anyway," the framework has no way to register it.

This is not a minor finding. It suggests that the entire edifice of soft power scholarship has been looking at the wrong thing. The interesting question is not "how much Korean content reached Vietnam?" but "what work is the signifier 'Korea' doing in Vietnamese contexts?"

D. There Is No "K" in the K-Thing

Here is the irony: Korean academics and nationalists have already noticed that in many of the most successful areas of K-cultural spread, "there is no 'K' in the K-thing." K-pop is assembled from global elements. Korean fashion is bricolage. Korean beauty standards are hybrid. The "Korean-ness" is in the curation and assembly, not the content.

But they have not completed the thought.

If "Korean" cultural products are already assemblages of non-Korean elements, and if receiving populations can produce "Korean-ness" without Korean content, then what we are tracking is not the spread of Korean culture but the circulation of a signifier. "Korea" has become a floating signifier available for deployment by anyone, anywhere, for purposes Korea cannot anticipate or control.

This is where the field should have gone. The soft power framework made it impossible to get there.

VII. From Soft Power to Korea as Signifier

A. The Critical Tradition We Build On

This article does not emerge from nowhere. A critical tradition already exists within and adjacent to Korean studies—one that has been raising these concerns for years, often against the grain of the field's dominant funding structures and common sense.

Koichi Iwabuchi pioneered the critique of nation-state-centric frameworks in East Asian media studies. His Recentering Globalization (2002) offered a "dialogic" approach to regional media flows that refused the unidirectional projection model, emphasizing how cultural products transform through circulation rather than simply spreading outward from national origins.

Chua Beng Huat, working with Iwabuchi, reframed the unit of analysis from national export to regional formation. Their edited volume East Asian Pop Culture: Analysing the Korean Wave (2008) treated the Korean Wave as a phenomenon of regional cultural traffic rather than Korean national achievement—a crucial methodological shift that soft power scholarship largely ignored.

Kyong Yoon has directly named what soft power discourse does: it functions as "a symbolic instrument to re-engineer Korea as a neoliberal nation-state." His work in Communication Research and Practice (2023) deconstructs the soft power framework's ideological operations, revealing how it serves Korean state interests while claiming analytical neutrality.

Youjeong Oh at the University of Texas at Austin has organized workshops explicitly titled "Decolonization of Korean Studies: Alternative Knowledge Production, Methods, and Praxes." Her initiative directly addresses the epistemic asymmetries this article describes—the positioning of Global South scholars as native informants rather than theorists.

The International Journal of Communication has published multiple critiques of "methodological nationalism" in Korean Wave scholarship, calling for approaches that do not treat the nation-state as the natural container of cultural processes.

Linus Hagström and Janice Bially Mattern, working in international relations theory, have demonstrated that soft power is neither soft nor innocent—that it enables hard power, that its rhetoric functions as coercion, that the soft/hard distinction is ideological rather than descriptive.

Hyunjung Lee's concept of the "global fetish" explains why Korean studies was so eager to adopt Western theoretical frameworks regardless of their analytical value—because Western validation satisfies the fetishized desire for global recognition.

This article synthesizes and extends this critical tradition. The scholars named above have been doing the work. What has been missing is consolidation—a clear alternative framework that can replace soft power rather than merely critique it. "Korea as Signifier" is offered in that spirit: not as a rejection of what came before, but as an attempt to give the critical tradition a positive program.

B. The Alternative Framework

What would it mean to study Korea as Signifier rather than Korean soft power?

It would mean, first, refusing the nation-state as the organizing unit of analysis. "Korea" in global cultural circulation is not identical with the Korean nation-state, Korean people, or Korean territory. It is a sign—available for deployment, capable of doing different work in different contexts, detachable from its supposed origins.

It would mean, second, treating semiotic slippage as the mechanism, not the failure. The soft power framework treats slippage as loss—if "Korea" starts meaning things Korea didn't intend, that's dilution, lack of message discipline, failure of branding. The Korea as Signifier framework recognizes that slippage is how cultural transmission actually works. When the signifier detaches and becomes available for local deployment, that's when it does cultural work. Control kills influence; release enables it.

It would mean, third, centering receiving-end perspectives as analytical positions. Scholars positioned in receiving contexts see what origin-point scholars cannot: the transformation, appropriation, and deployment of signifiers for local purposes. This is not "including more perspectives." It is recognizing that certain knowledge is only available from certain positions.

It would mean, fourth, asking new questions. Not "how much Korean content reached foreign markets?" but "what work does the signifier 'Korea' do in different contexts?" Not "is Korea's soft power increasing?" but "how is the category 'Korea' being deployed, by whom, for what purposes?"

C. What the Framework Reveals

The Korea as Signifier framework makes visible:

Signifier zones: Where is "Korea" being deployed? By whom? With what content attached—or not attached?

Semiotic slippage: Where has the signifier detached from Korean content? What does it mean when people produce "Korean-ness" without Korea?

Local labor: The creative work of receiving populations in deploying, transforming, and investing meaning in the signifier. This labor has been invisible in soft power analysis.

The paradox of influence: A floating signifier that people want to use for their own purposes is more valuable than a controlled brand message nobody cares about. Every time someone styles something as "Korean" without Korean content, they are investing in the category—doing distributed cultural labor that ultimately accrues back to Korea.

D. A Better Story for Korea

Here is what Korean institutions need to understand: Your influence is bigger than you think, but you're measuring the wrong thing.

Soft power analysis counts content exports. It measures market penetration. It surveys favorable attitudes toward Korea. All of this misses the actual mechanism of cultural influence.

When Vietnamese youth style spaces as "Korean" without Korean products, when Indonesian women perform "Korean fashion" without Korean brands, when Filipino dancers embody "Korean" movement vocabularies—they are not passively receiving Korean culture. They are using the signifier for their own purposes. And in doing so, they are making "Korea" mean something desirable in their context.

This is not dilution. This is distributed cultural labor. It is more valuable than any export statistic.

The soft power framework cannot see this because it can only see Korean intention and Korean content. The Korea as Signifier framework sees the signifier's autonomous life—and recognizes that autonomy as strength, not weakness.

VIII. New Vocabulary for New Questions

A. What We're Abandoning

Penetration — Sexual/military violence; figures audiences as bodies to be entered

Capture — Denies agency; treats audiences as prey

Conquest — Military campaign; treats cultural spread as warfare

Cultural weapon — Instrumentalizes culture for attack

Strategic deployment — Military operations language

Triumph — Zero-sum framing; Korea wins, others lose

Target market — Audiences as things to be hit

B. What We're Developing

Korea as Signifier — The category "Korea" as sign, available for deployment, detachable from content

Semiotic slippage — When the signifier operates independently of Korean content or intention

Signifier zones — Contexts where "Korea" is being deployed—with or without Korean content

Receiving-end epistemology — Knowledge production from positions where signifiers arrive and transform

Distributed cultural labor — The work receiving populations do in deploying and investing meaning in signifiers

Transculturation — Mutual transformation of cultural elements in contact (from Fernando Ortiz)

Kinesthetic transmission — Embodied learning through practice rather than conscious adoption

C. Why Vocabulary Matters

How we talk shapes what we can think. The violent vocabulary of soft power makes cultural imperialism look like neutral description. It makes domination feel like success. It makes receiving populations disappear into statistics about Korean achievement.

New vocabulary is not political correctness. It is the condition of possibility for seeing what the old vocabulary hid.

IX. Conclusion: The Choice

A. Two Frameworks

Unit of analysis: Soft Power sees the nation-state; Korea as Signifier sees the signifier

Key question: Soft Power asks "How much Korean content reached foreign markets?"; Korea as Signifier asks "What work does the signifier 'Korea' do?"

Flow model: Soft Power assumes unidirectional flow (Korea → world); Korea as Signifier sees multidirectional transformation

Receiving populations: Soft Power treats them as targets, audiences, markets; Korea as Signifier recognizes them as agents, producers, deployers

Semiotic slippage: Soft Power sees failure and dilution; Korea as Signifier sees the mechanism and strength

Success metric: Soft Power measures penetration, capture, favorable attitudes; Korea as Signifier tracks signifier deployment and distributed labor

Epistemology: Soft Power privileges origin-point perspectives (Seoul, Western academy); Korea as Signifier centers receiving-end positions (where signifiers arrive)

Vocabulary: Soft Power uses penetration, conquest, capture; Korea as Signifier uses slippage, deployment, transculturation

B. What's at Stake

The soft power framework has made Korean studies, in its popular culture wing, an intellectual apparatus for celebrating Korean cultural expansion. Scholars trained in critical methods have somehow accepted "penetration" and "conquest" as neutral analytical terms. This is not a failure of intelligence. It is a failure of reflexivity—a failure to interrogate the common sense that organizes the field.

When scholarship adopts the vocabulary of violence without comment, it normalizes the idea that cultural exchange is cultural warfare. When it measures "success" by market domination, it makes domination the goal. When it treats receiving populations as targets, it erases their agency and their labor.

The Korea as Signifier framework is not merely a methodological refinement. It is an ethical imperative. And it is also, frankly, more interesting. Soft power can only ask one question and can only see one thing. Korea as Signifier opens:

New questions (what does the signifier do?)

New evidence (receiving-end perspectives, slippage zones)

New objects (transformation, deployment, distributed labor)

New collaborations (Global South scholars as theorists, not informants)

C. The Invitation

The soft power paradigm is exhausted. Its vocabulary is violent. Its epistemology is closed. Its institutional supports align it with state interests rather than critical inquiry.

We can continue celebrating Korean "conquest" of foreign markets. Or we can ask what is actually happening when the signifier "Korea" travels, transforms, and does work in the world.

From Soft Power to Korea as Signifier.

The choice is ours.

Coda: The Graveyard of Slogans

Before soft power scholarship convinced Korean institutions they were successfully "penetrating" global markets, there was nation branding—and it left behind a graveyard.

"Dynamic Korea." "Korea Sparkling." "Korea, A Loving Embrace." "Creative Korea." "I.Seoul.U." Each slogan launched with ministerial fanfare; each quietly abandoned or scrapped within years.

The Presidential Council on Nation Branding, established in 2009 with an $81 million annual budget and 47 advisers including eight cabinet ministers, was abolished in 2013. It lasted exactly one presidential term. The $20 million "Globalization of Hansik" campaign—bibimbap commercials in Times Square, K-pop groups singing about Korean food—was judged "an utter failure" by the National Assembly. The "Korea Sparkling Widget" featured a cartoon foreigner getting kicked in the testicles, hit with sticks, and having his head explode from eating Korean food. This was official government outreach.

The Korea Times called "Korea Sparkling" "cringe-worthy." The head of the nation branding council himself admitted it had "limited impact."

This is what centralized brand control produces: institutional churn, wasted budgets, and international embarrassment. The signifier "Korea" became globally desirable not because of these campaigns but despite them—through processes the branding apparatus could neither anticipate nor control.

Soft power scholarship learned nothing from this history. It simply moved the fantasy of control from slogans to "strategic deployment" of cultural content. The vocabulary changed; the delusion persisted.

You cannot control what "Korea" means. The graveyard of slogans proves it. The only question is whether the field will keep measuring "penetration" of markets that were never penetrated, or finally ask what the floating signifier is actually doing in the world.

References

"Korea's Branding Woes." The Diplomat, October 26, 2014. https://thediplomat.com/2014/10/koreas-branding-woes/

Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. "The Case for South Korean Soft Power." December 2020.

Chua, Beng Huat, and Koichi Iwabuchi, eds. East Asian Pop Culture: Analysing the Korean Wave. Hong Kong University Press, 2008.

Cicchelli, Vincenzo, and Sylvie Octobre. The Sociology of Hallyu Pop Culture: Surfing the Korean Wave. Palgrave Macmillan, 2021.

Dunbar, Jon. "Have you ever … produced propaganda?" Korea Times, August 10, 2018. https://www.koreatimes.co.kr/opinion/20180810/have-you-ever-produced-propaganda

Hagström, Linus. Research on soft power and hard power linkages. Swedish Defence University, 2019.

International Journal of Communication. Multiple articles critiquing methodological nationalism in Korean Wave scholarship.

Iwabuchi, Koichi. Recentering Globalization: Popular Culture and Japanese Transnationalism. Duke University Press, 2002.

Jin, Dal Yong. New Korean Wave: Transnational Cultural Power in the Age of Social Media. University of Illinois Press, 2016.

Jin, Dal Yong. "The Rise of Digital Platforms as a Soft Power Apparatus in the New Korean Wave Era." SAGE Open, 2024.

"'Creative Korea' slogan lacks creativity, consistency." Korea Times, July 6, 2016.

Lee, Geun. "A Soft Power Approach to the 'Korean Wave.'" The Review of Korean Studies 12, no. 2 (2009): 123-137.

Lee, Hyunjung. "Global Fetishism: Dynamics of Transnational Performances in Contemporary South Korea." PhD dissertation, University of Texas at Austin, 2008.

Lee, Hyunjung. Performing the Nation in Global Korea: Transnational Theatre. Palgrave Macmillan, 2015.

Mattern, Janice Bially. "Why 'Soft Power' Isn't So Soft: Representational Force and the Sociolinguistic Construction of Attraction in World Politics." Millennium 33, no. 3 (2005).

Montgomery, Charles. "Korea, Sparkling Widget." Korea Times, February 3, 2009. https://www.koreatimes.co.kr/www/opinion/2024/12/137_38868.html

"Nation Branding: Shaking Off the Korea Discount." Knowledge at Wharton, January 12, 2011. https://knowledge.wharton.upenn.edu/article/nation-branding-shaking-off-the-korea-discount/

Nye, Joseph S., and Yuna Kim. "Soft Power and the Korean Wave." In South Korean Popular Culture and North Korea, edited by Youna Kim. Routledge, 2013.

Oh, Youjeong. "Decolonization of Korean Studies: Alternative Knowledge Production, Methods, and Praxes." Workshop, University of Texas at Austin, 2024.

Petras, James. "Cultural Imperialism in the Late 20th Century." Global Policy Forum, 2000.

Presidential Council on Nation Branding. Wikipedia. https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Presidential_Council_on_Nation_Branding,_Korea

Schiller, Herbert. Communication and Cultural Domination. International Arts and Sciences Press, 1976.

Yoon, Kyong. "De/Constructing the Soft Power Discourse in Hallyu." Communication Research and Practice, 2023.

AI Research Methodology Statement

This article was produced using AI-assisted research methodology. Dr. Michael Hurt controlled the entire research and writing process, providing all intellectual direction, theoretical positioning, argument development, and analytical interpretation based on his expertise in Korean studies methodology and extensive fieldwork across South Korea, Vietnam, Indonesia, and the Philippines. Claude AI (Anthropic) functioned as an advanced research assistant for literature review, source identification, and drafting under direct expert supervision. All scholarly judgments, theoretical frameworks, and critical assessments reflect Dr. Hurt's academic expertise. This methodology statement follows emerging best practices for transparent disclosure of AI assistance in academic research, as developed at Stanford, MIT, and University of California institutions.