The “Korean” Cat Café That Wasn't Korean: A Discovery in Hanoi's Hidden Cultural Laboratory

Or, how a wrong turn in socialist housing revealed the quiet mechanics of global culture

1. Following the Fixer

My fixer was insistent: there was a cat café I needed to see.

This recommendation made perfect sense in the context of my ongoing research project tracking Korean cultural influence across Asia. Cat cafés are closely associated with Japanese kawaii culture and nowadays cool Korean cat cafes that are heavily promoted in the tourist zones of Seoul such as Myeongdong, part of the broader wave of East Asian aesthetic trends that have been reshaping urban spaces from Seoul to Jakarta. Using what I call "photo-sartorial elicitation" — photographing models styled in what they believe represents "Korean fashion" while they navigate uniquely local spaces — I had been documenting how Korean cultural elements actually move through the world.

So when my Hanoi fixer recommended a cat café, I expected to find exactly what I'd been used to seeing: a clean, Instagram-ready space filled with cute cats, pastel colors, and the kind of calculated charm that characterizes Korean-influenced commercial spaces across Southeast Asia.

The cat café — which notably, I never got the name of ( and I later conlcuded wasn’t truly a cat café in the sense I had been thinking at the time, but rather I think the place just had a couple cats living there)— was strangely…homey. This is because, I would soon find out, it was literally built inside a residential housing unit, which explained why the place was so hard to find.

Instead, my fixer led me deep into what seemed like a residential maze—narrow alleys, aging concrete buildings, the kind of everyday urban reality that doesn't normally cater to cultural tourism or aesthetic experimentation. When we finally made it to the cat café, it was tucked into the third floor of what looked like an American, “projects”-style apartment block. A few cats wandered lazily between simple tables and chairs. And when I asked about the Korean influence that had led to this recommendation, the owners seemed genuinely puzzled.

"We're not trying to be Korean," they told me directly. More puzzling still, they seemed genuinely disinterested in having any publicity about their establishment.

This wasn't supposed to happen.

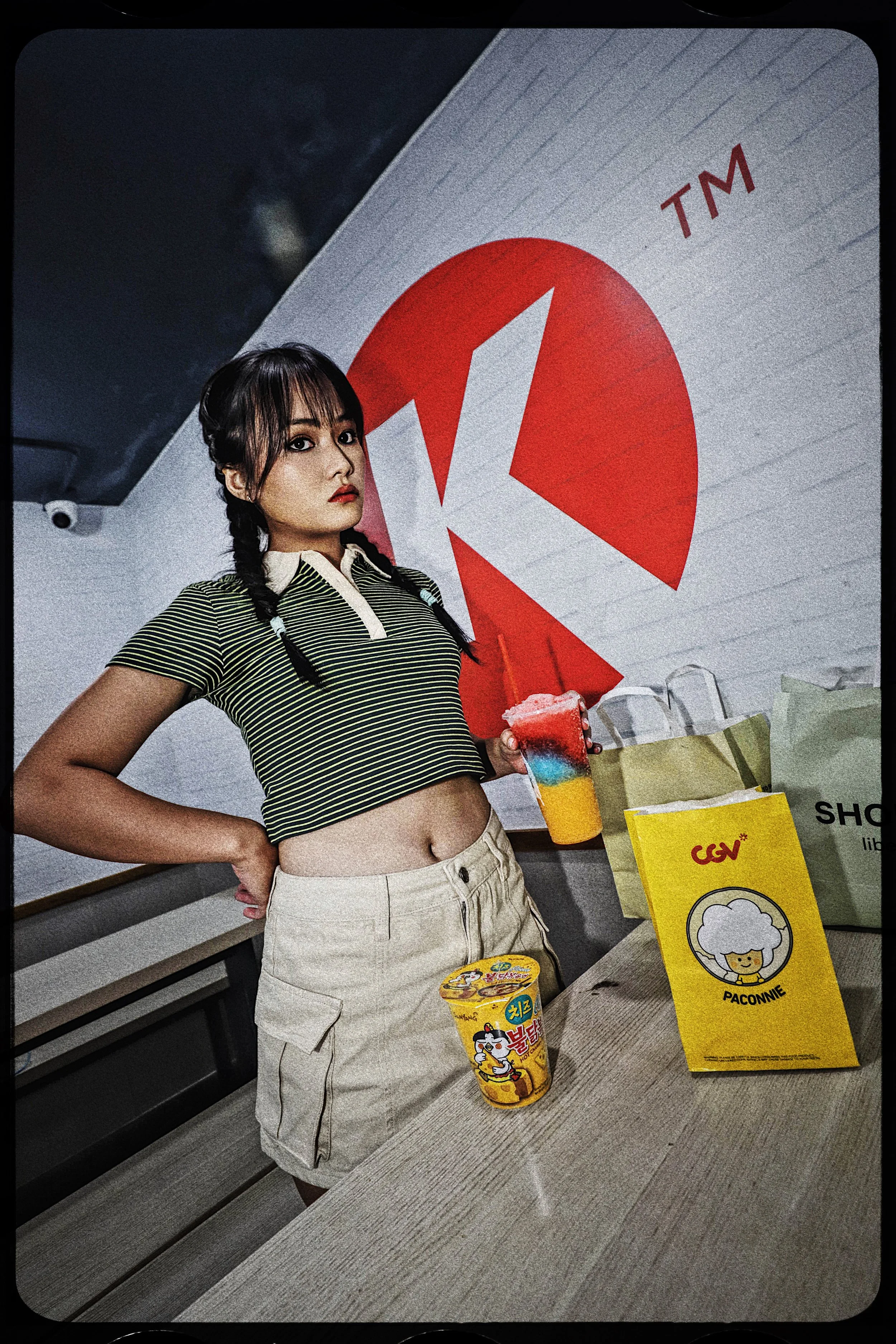

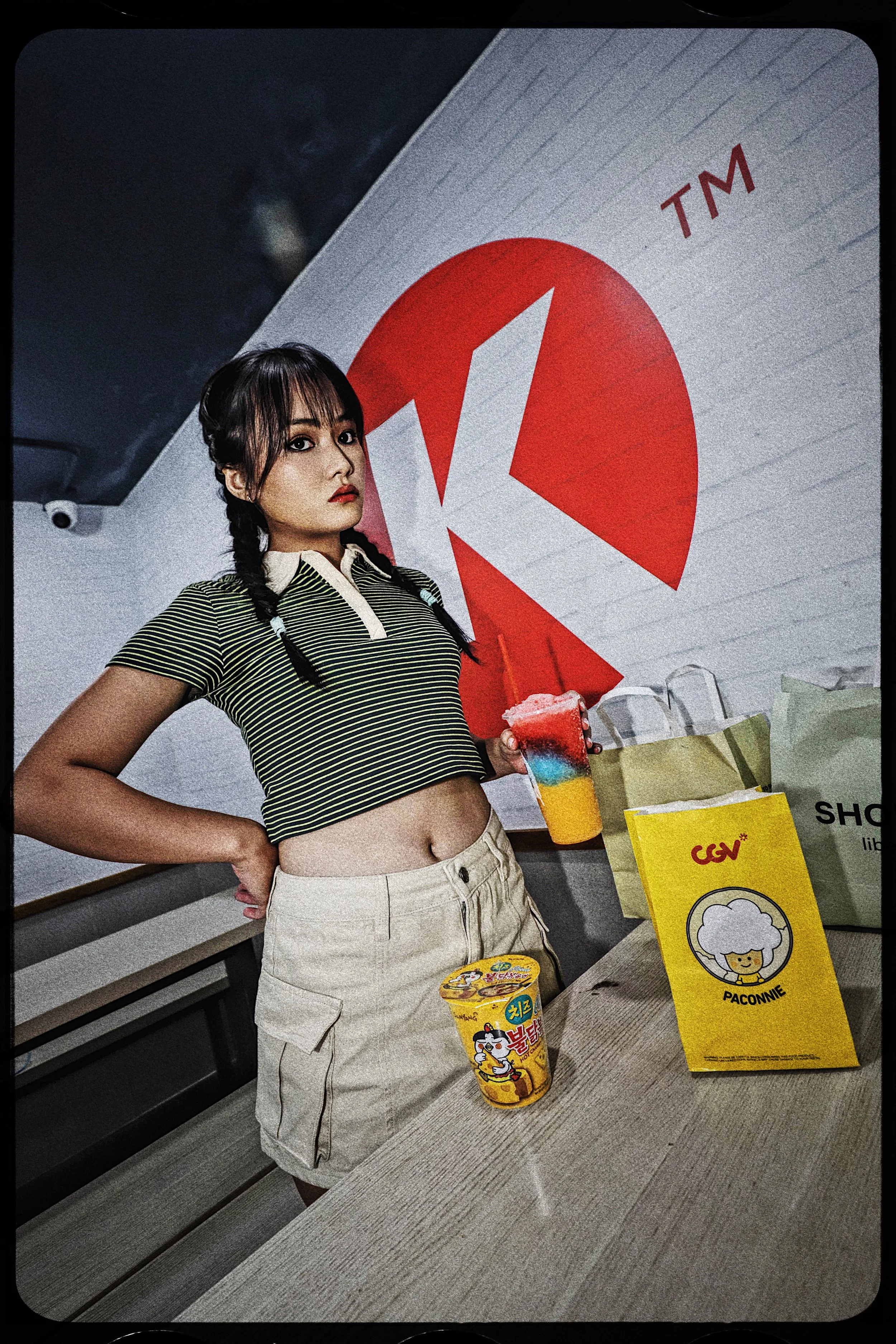

Inside the extremely Vietnam-localized KTT complex near the residential/student-vibey area of the Đống Đa district of Hà Nội, near the Hanoi Medical University Hospital.

What struck me as particularly interesting was that the owners seemed genuinely disinterested in having any publicity about their establishment. Most businesses influenced by global aesthetic trends — especially Korean trends — usually embrace the visibility and cultural cachet that comes with that association. They want to be photographed, shared on Instagram, and recognized as part of international cultural networks.

That moment of confusion — when expectations collide with reality — often signals that something more interesting is happening than what you originally planned to study. In research methodology, we sometimes call this "productive failure": when your research plan falls apart in ways that reveal patterns you never would have discovered if everything had gone according to plan (Debord, 1958).

What I didn't realize yet was that I had stumbled into one of the most fascinating cultural laboratories in contemporary Asia: a place where traditional Vietnamese spatial practices, socialist planning legacies, and global aesthetic influences were negotiating complex relationships in ways that challenged everything I thought I understood about how culture moves through the world.

Local Vietnamese model My Tien (@_midnight_mt) wearing LIBÉ Workshop (@libeworkshop)'s signature "simple and clean" minimalist aesthetic positioned against the weathered concrete walls and exposed infrastructure demonstrates how sophisticated alternative cultural expression flourishes within an authentic Vietnamese neighborhood envirronment of the the Đống Đa KTT complex. Though LIBÉ Workshop (@libeworkshop) describes itself as creating "basic and essential products," Vietnamese consumers, tourism sites, and fashion retailers consistently categorize the brand as exemplifying "Korean style" (Mytour, 2024; SilverKris, 2024)—revealing how minimalist aesthetics automatically code as "Korean" in a Vietnamese cultural context, and can embody a contrast between contemporary styling and raw socialist-era urban infrastructure.

2. Tracking Cool Across Asia

For several years, I've been conducting what I call "photo-sartorial elicitation" across Asia, a methodology that sounds more complicated than it is — essentially photographing models styled in what they believe embodies "Korean fashion" while they navigate certain kinds of spaces to make sense of the spatial-sartorial conversation that inevitably follows. In international contexts, I work with local models who dress in what they consider Korean style, then photograph them in “interesting” locations in their city. The goal is simple: to understand how Korean culture actually moves through the world, and not just how academics or policy makers think it does — or should — according to pre-existing frames of thinking.

Photo-sartorial elicitation methodology scaffolds aspiring Vietnamese teen model @_pngan.n into showing her interpretation of “Korean style” in Hanoi in February 2020, embodying the combined stylings of her mom, a separate makeup artist, and our fashion industry fixer.

Extending the same photo-sartorial prompt into the summer of 2025, model @_pngan.n channels a much more exact, Korean-styled look that is much more in direct conversation with Seoulish trends and her newer, more mature sensibilities as a full-grown, working model regularly shooting in multiple projects.

The project had taken me from Saigon to Seoul, from Danang to Yogyakarta, and each location revealed different aspects of how "Korean" aesthetics get translated and adapted locally. In Yogyakarta, many Indonesian Muslim women had developed sophisticated "safe space strategies" — spatial and temporal calculations that enabled Korean aesthetic rebellion within religious boundaries. Coffee shops during evening hours, specific mall environments, and K-pop events functioned as "cultural permission zones" where young women could experiment with global aesthetics while maintaining religious authenticity (Hurt, 2025).

A youth hangout — a popular “Korean”-style coffee shop — in Yogyakarta, Indonesia back in July 2023. In a majority Muslim country that has a fraught relationship with bars and other places that sell alcohol, a cool coffee shop replaces the bar or nightclub, as it does here at the Cosan Seturan coffee shop on a late Friday night.

In Yogyakarta, Indonesia, “Aminah”, a fairly observant Muslim woman, felt free to walk around without a hijab, dressing in what I instantly recognized as full-on “K-Style”, which was confirmed after asking her for an interview. But she reluctantly only agreed to a picture after getting the promise that her face would be cut out due to the fact that her look was what she considered too risqué for public consumption.

In Danang, I discovered that "Korea" functioned as what locals called "a tool to think about how to be a cool Asian" — a framework for accessing aspirational coolness that transcended actual Korean cultural content. Whether people were consciously channeling Korean aesthetics or not, Korean modes or items were considered "unquestionably cool," suggesting the ubiquity of "Korean cool" as a cultural category that extended far beyond actual Korean cultural origins (Hurt, 2025).

In Danang in 2018, That shirt led me to pull her aside for an interview and picture. She didn't think of it as “Korean” herself, but it turns out she bought it in a bricks and mortar store called L-Seoul. She said she bought it because it was “just pretty.” This was indicative of a pattern I was finding as I interviewed more folks in Vietnam doing what I saw as Korea-influenced things.

But Vietnam was different. Every location I visited that locals described as "Korean influenced" seemed to contain aesthetic elements that had little to do with Korea. The famous Nậu Café & Cassette Workshop—recommended by three different people as the perfect example of Korean aesthetic influence in Hanoi — was filled with American hip-hop culture from the 1980s and 90s, vintage Americana, and analog retro elements that drew more from Brooklyn's artisanal coffee scene than Seoul's café culture (Hurt, 2025).

The interior of the Nậu Cafe & Cassette Workshop (@naucassette.cafe), which is filled with vinyl records, retro/old audio equipment, and other pieces of Americana aesthetics — which somehow also maps onto hip-hop style for many of the customers there.

At first, I thought people were confused about the cultural origins of certain elements of the spaces. Maybe Vietnamese consumers couldn't distinguish between different international influences. Maybe they were mislabeling American or European aesthetics as Korean. But the more I researched, the more I realized something far more sophisticated was happening: Vietnamese actors weren't confused about cultural origins at all — they were demonstrating advanced cultural curation skills, actively using "Korean" as an organizational framework for accessing global aesthetics that felt both cosmopolitan and authentically Asian.

This realization led me to develop what I came to call the "Cultural DJ Theory": Korea functions not as a cultural producer exporting pure Korean content, but as a cultural DJ, sampling and rebranding global aesthetic elements under Korean authority. Korean cultural industries don't export Korean culture; they export curated global culture under Korean branding. And Vietnamese consumers weren't passively receiving Korean culture—they were sophisticated enough to understand that "Korean coolness" had become a delivery system for global aesthetics, and they were actively curating those global elements according to their own cultural logic.

Between self-identification and cultural categorization: My Tien (@_midnight_mt) holds a slushie in a Vietnamese Circle K, wearing LIBÉ Workshop (@libeworkshop)'s designs that exemplify the gap between brand intention and consumer interpretation. While the brand describes offering "exclusive Vietnamese designs" using "timeless pieces which blend simplicity with character" (SilverKris, 2024), Vietnamese fashion guides and retailers consistently read this minimalist approach as "Korean style" (Mytour, 2024; Mytour, n.d.), revealing how cultural translation operates through established frameworks where raw socialist infrastructure encounters contemporary styling organized through "Korean" as shorthand for sophisticated global aesthetic engagement.

But I still didn't understand why this cultural translation process was happening so systematically in Vietnam, or what made Vietnamese spaces such effective sites for this kind of cultural remixing. The answer, it turned out, lay in the historical and architectural context I had stumbled into without realizing it: the complex world of Vietnamese socialist urban planning and the remarkable spaces it created.

3. The Complex That Time Forgot

The cat café wasn't located in just any residential complex. As I began investigating the architectural context, I realized I was sitting in the middle of one of Vietnam's most significant urban experiments: a Khu Tập Thể (KTT) collective housing complex — a socialist-era residential development designed to create new forms of community life under revolutionary urban planning principles.

KTT literally translates as "collective districts" — comprehensive residential communities built by the Vietnamese state between the 1960s and 1990s to house workers, civil servants, and military personnel (Le & Nguyen, 2020). These weren't just apartment buildings; they were designed as complete socialist communities featuring integrated schools, markets, healthcare facilities, and community centers for "nation building" activities. The entire development was intended to create "new socialist persons" through architectural control of daily life (Schwenkel, 2020).

Wide shot of a Khu Tập Thể (KTT) collective housing complex in the Đống Đa district of Hà Nội, Vietnam showing the scale and organization of the development.

Walking through the complex, the original socialist planning vision becomes visible in the spatial organization: standardized 3-5 story apartment blocks featuring extremely small units (9-35 square meters) with shared facilities, central courtyards designed for collective activities, and the systematic integration of work, living, and social functions within single developments (Trinh, 2019). The famous mustard yellow facades that characterize many Hanoi KTT complexes create a distinctive visual identity that marks these spaces as products of a specific historical moment and political vision.

A rough overview and map of the area, with reference to some of the images of our photo-sartorial “drift” through the space.

But what makes these spaces fascinating isn't their original design—it's what residents have done with them since Vietnam's 1986 Doi Moi economic reforms fundamentally transformed the country's relationship to private property and global markets. The rigid socialist housing has been converted into dynamic mixed-use neighborhoods through resident-led modifications that demonstrate remarkable spatial creativity and cultural adaptation.

Informal extensions called "tiger cages" (chuồng cọp) — corrugated sheet, brick, or lattice additions — expand living space and create commercial opportunities (Le & Nguyen, 2020). Ground-floor residential units have been converted to shops, cafes, restaurants, and service businesses. Upper floors have expanded through suspended balconies and corridor appropriations. What emerges is a form of "xây chen" (squeezed-in construction) where residents systematically fill spaces between existing blocks with new structures, creating denser urban infrastructure while maintaining community functions (Nguyen, 2018).

Community-embedded commerce: Model My Tien (@_midnight_mt) wears LIBÉ Workshop (@libeworkshop)'s "basic and essential" minimalist designs positioned within an embedded retail shop, demonstrating how authentic Vietnamese retail culture operates within residential-commercial hybrid environments. While LIBÉ Workshop (@libeworkshop) positions itself as providing "products for everyone to build their style," the brand appears consistently in Vietnamese "Korean-style fashion" guides and is recommended by retailers as exemplifying a Korean aesthetic (Mytour, 2024), revealing how minimalist design vocabularies become automatically coded as "Korean" in the Vietnamese cultural context, and helps transform socialist housing into spaces where global aesthetic categories can find an easy aesthetic fit with local commercial practices.

The cat café, I realized, wasn't an isolated business; it was part of a broader ecosystem of resident-driven commercial activities that had transformed these socialist spaces into vibrant mixed-use communities. And this transformation wasn't random — it followed distinctly Vietnamese patterns of spatial use that had persisted through decades of socialist planning and were now shaping how global cultural influences got incorporated into local contexts.

4. Building the Socialist Dream

Desolate minimalism meets contemporary fashion: My Tien (@_midnight_mt) inhabits the raw aesthetic of Soviet-influenced KTT construction, where exposed electrical panels and weathered concrete walls create an unintentionally minimalist backdrop for editorial fashion photography. Her LIBÉ Workshop (@libeworkshop) styling — characterized by the brand as "basic and essential products" yet consistently categorized as "Korean style" by Vietnamese sources (Mytour, 2024; Mytour, n.d.) — gains conceptual power against this austere socialist infrastructure. The desolate interior, originally designed for collective functionality rather than individual expression, becomes a striking editorial environment where contemporary Vietnamese fashion sensibilities encounter the stripped-down materiality of revolutionary urban planning, transforming utilitarian socialist space into sophisticated aesthetic context for global style vocabularies.

To understand how these spaces became such effective laboratories for cultural translation, you need to understand their remarkable origin story. The KTT system represents one of post-war Asia's most ambitious urban experiments: an attempt to create new forms of human community through revolutionary architecture and planning.

The story begins in the devastation of post-war Vietnam. After reunification in 1975, the new Socialist Republic faced massive reconstruction challenges while simultaneously trying to build a new society based on collective principles rather than individual property ownership. Traditional Vietnamese urban forms — the narrow shop-houses and courtyard compounds that characterized places like Hanoi's Old Quarter — were seen as embodying feudal and colonial spatial relationships that the revolution needed to transcend.

Vietnamese planners looked to the Soviet Union for inspiration, but they didn't simply copy Soviet models. The rebuilding of Vinh City, completely destroyed by US bombing, became Vietnam's first experiment in planned socialist urbanism. With East German technical assistance, Vinh was reconstructed featuring monofunctional zoning, massive housing estates, and integrated industrial development. But Vietnamese architects notably rejected Stalinist monumental architecture in favor of functional modernism better suited to the tropical climate and local cultural preferences (Schwenkel, 2020).

A typical Soviet-style block in Riga, Latvia [source]

The theoretical foundation drew heavily from Soviet microrayon concepts — comprehensive residential districts containing all necessary social services within walking distance. But Vietnamese adaptations incorporated their own distinctive features: climate-responsive design modifications, including vernacular pitched roofs for monsoon rains, integration with traditional Vietnamese spatial hierarchies, and accommodation of extended family structures despite units originally designed for nuclear families.

Between 1958-1990, Hanoi alone constructed 30 KTT developments covering 4.5 million square meters and housing over 125,000 apartments (Le & Nguyen, 2020). The famous Kim Liên KTT, built from 1960-1970, covered 42 hectares and was originally planned for 7,000 residents. These weren't just housing projects — they were comprehensive urban communities designed to create new forms of socialist citizenship through daily spatial practice.

The apartments themselves embodied a collective living philosophy. Shared kitchens and bathrooms served multiple families, forcing residents into daily cooperation over basic life functions. Common areas were designed for "nation-building" activities — political meetings, cultural performances, collective celebrations. The integration of work, living, and social functions within single developments reflected socialist principles that individual and community development were inseparable.

Model My Tien (@_midnight_mt) in LIBÉ Workshop (@libeworkshop)'s minimalist "basics with character" occupies abandoned playground infrastructure within the KTT complex, highlighting the space’s transformation from collective socialist spaces to sites of individual cultural agency.

But here's what makes the story fascinating: despite being designed to create "new socialist persons," these spaces became remarkably effective at preserving and adapting traditional Vietnamese cultural practices (Thomas, 2002). Multi-generational families navigated small living spaces through flexible arrangements that maintained traditional hierarchical social relationships. Home altars for ancestor worship were maintained within modern units. Communal dining practices utilized shared spaces in ways that preserved traditional social patterns within revolutionary architectural contexts (Drummond, 2000).

The result was a unique hybrid: spaces that were socialist in their planning principles but Vietnamese in their lived experience. And this hybrid character—this capacity to blend international planning models with local cultural practices — would prove crucial when these communities encountered global cultural influences during Vietnam's economic opening after 1986.

5. The Cultural DJ Booth

Strange things are indeed afoot at the Circle K: My Tien (@_midnight_mt) inhabits a space that exemplifies complete cultural localization/naturalization, where American convenience store infrastructure has been so thoroughly adapted to Vietnamese social practices that its foreign origins become invisible. Vietnamese consumers have localized this space through distinctive usage patterns — extended socializing, homework sessions, informal meetings — transforming what began as grab-and-go retail into community gathering places that function more like traditional Vietnamese café culture than American convenience stores.

The breakthrough in understanding what I was observing came when I realized that the KTT complexes weren't just sites where Korean cultural influence was being translated—they were sophisticated cultural laboratories where Vietnamese residents were actively curating global aesthetic vocabularies according to their own cultural logic, using "Korean" as a trusted brand for accessing cosmopolitan coolness.

This is where the "Cultural DJ Theory" becomes essential to understanding contemporary cultural globalization (Hurt, 2025). Just as a DJ doesn't create original music but instead samples, recombines, and recontextualizes existing musical elements to create new aesthetic experiences, Korean cultural industries function as cultural DJs on a global scale. They systematically appropriate American hip-hop aesthetics, Japanese kawaii culture, European fashion trends, and other international cultural elements, then integrate them into "Korean" aesthetic packages that get exported globally under Korean cultural branding (Kim, 2015; Lie, 2015).

The process works through what can be called an "Appropriation-Rebranding Feedback Loop" (Hurt, 2025):

Seoul appropriates global cultural elements (American hip-hop, vintage aesthetics, Scandinavian minimalism)

Integrates them into "Korean" aesthetic packages (Korean cafés with hip-hop elements, K-pop with American influences)

Exports these hybrid aesthetics globally under "Korean" cultural branding

Global audiences interpret appropriated elements as "authentically Korean"

Seoul reinforces this interpretation, establishing Korean identity as a master brand for internationally sourced aesthetics

The result is that Korean cultural identity becomes associated with aesthetics that actually originate elsewhere (Saeji, 2018). Multiple Hanoi cafés described as having "Korean style" featured design elements more closely associated with Scandinavian minimalism or American industrial aesthetics. However, these elements had been filtered through Korean cultural packaging and were genuinely perceived as Korean by Vietnamese consumers.

But here's what's crucial: Vietnamese consumers weren't confused about this process — they understood it perfectly. They recognized that "Korean coolness" had become a delivery system for global aesthetics, and they were actively curating those global elements according to Vietnamese cultural frameworks.

The KTT complexes proved to be ideal spaces for this kind of cultural curation because of their unique spatial characteristics. These developments had always been sites where international planning models encountered Vietnamese cultural practices to create new hybrid forms. Residents had forty years of experience adapting foreign spatial concepts (Soviet microrayons) to Vietnamese social needs through creative modification and informal appropriation.

When global cultural influences began entering Vietnam after Doi Moi, residents of these complexes applied the same skills they had developed for spatial adaptation to cultural translation. They selectively incorporated global aesthetic elements while maintaining Vietnamese social functions. Cafés adopted Korean visual vocabularies while preserving Vietnamese patterns of community interaction. Commercial spaces embraced international design trends while continuing to function as extensions of neighborhood social life.

Even the exterior of the “Korean” Nậu Cafe & Cassette Workshop integrates Vietnamese spatial practices into "Korean" influenced spaces - but note that the low chairs, abundant plants, and community use pattern of seating is aat the front of the store, before entering the “Korean” (global/international) zone.

The cat café that started this investigation exemplified this process perfectly. Local people recommended The Nau Cafe as the best example of Korean café culture not because it actually looked Korean, as in hanbok or wooden hanok construction, but because it successfully used the category "Korean" to organize a sophisticated selection of global aesthetic elements — American retro culture, vintage audio equipment, analog photography gear—in ways that felt both cosmopolitan and authentically local.

What I was witnessing wasn't cultural confusion or the passive consumption of Korean exports. It was active cultural production: Vietnamese actors using their sophisticated understanding of how global cultural networks operate to create new hybrid forms that served their own community needs while participating in transnational cultural conversations.

6. When Spaces “Lie” About Their Origins

The implications of this discovery extend far beyond cafés in Hanoi or even Korean cultural influence in Southeast Asia. What I stumbled into through that cat café recommendation was evidence of a fundamental shift in how global culture operates—a shift that challenges basic assumptions about cultural authenticity, national cultural identity, and the mechanics of cultural influence in our interconnected world.

The conventional narrative about cultural globalization assumes that culture flows from production centers (like Seoul, Tokyo, or Hollywood) to consumption markets (like Hanoi, Jakarta, or Manila) through processes that are essentially one-directional (McGee, 2009). Cultural industries in dominant countries create content that gets distributed globally, and local populations either adopt or resist these foreign influences. This model treats culture like commodities: products manufactured in one place and consumed in another.

But what the Vietnamese case reveals is that this model fundamentally misunderstands how contemporary cultural networks actually operate. Culture doesn't flow in simple linear directions from producers to consumers. Instead, it moves through complex multi-directional networks where every node—every local community, every individual cultural actor—functions simultaneously as consumer and producer, translator and creator.

The mechanics of this process become strikingly clear when examining specific Vietnamese businesses that locals identify as exemplifying Korean style. SOYOUNG, a fashion boutique in Hanoi that multiple residents recommended as the city's best source for Korean fashion, provides a perfect case study of how this cultural translation operates in practice.

Walking into SOYOUNG, the aesthetic immediately signals "Korean style" to Vietnamese consumers: bold graphic prints, oversized silhouettes, street-influenced cuts, and the kind of statement pieces that characterize contemporary Korean fashion exports. The staff confirmed that customers explicitly seek out "Korean fashion" and understand SOYOUNG's inventory as representing authentic Korean style trends. But examining the actual aesthetic vocabulary reveals something more complex: the design elements that Vietnamese consumers identify as distinctly Korean trace directly to American hip-hop streetwear aesthetics of the 1990s and early 2000s.

This becomes particularly evident when comparing SOYOUNG's offerings with Korean brands like Greedilous, founded by Park Yeon Hee and worn by artists like Beyoncé, who famously bought "an entire rack" of Greedilous clothes during the brand's New York Fashion Week debut (Glossy, 2021). Greedilous exemplifies the Korean fashion industry's systematic appropriation of American hip-hop aesthetics—bold colors, oversized fits, graphic-heavy designs, and street culture references—integrated into "Korean" fashion packages and exported globally under Korean cultural branding.

*[IMAGE PLACEHOLDER: Multi-part photo series showing the cultural translation process:

The SOYOUNG main showroom and flagship store, which we were told was “super Korean.”

As soon as Odette was fully styled and posed up next to the SOYOUNG flagship store’s giant kitty mascot centerpiece, I was prompted to raise my main strobe high and off-center to simulate what my mind’s eye remembered as an early-2000s era Girl’s Generation album cover.

SOYOUNG’s styling on Odette was giving Austin Powers, nostalgia atop a layer of nostalgia, shiny PVC boots-and-thighs, Bond Girl long locks, in-Technicolor™ vibes.

But the best way to think about what the space’s spatial logic was is by listening to the main stylist/visual designer in the store, who styled up our model in the most elaborate work of photo-sartorial elicitation we’ve ever done, which resulted in a convergence of prompted style expression of what “Korean” is thought to be, but also by my own photographic choices in thinking of the affair as “Korean”, as well as what a Korean model in Vietnam thought after bring dressed up as a Korean by a Vietnamese stylist.

BUt even more than the visual, embodied text we all collaborated in producing, the words of Honey — the stylist herself — are instructive here, in this following transcript snippet:

[00:03:34] Michael : So can I ask you what what Vietnamese people, what another person might think of as Korean? Yeah. Especially since other people describe this place as a Korean place. What do you think makes them think that?

[00:03:50] Honey: It's definitely because of K-pop. Yeah, it's very like again, it's like stage clothes. It's it's stuff that you wear on stage. Mhm. Yeah. And uh, I think this brand influenced by that a lot. Because like normal, like normal people, they don't wear this kind of clothes like on a daily basis. Yeah.

[00:04:16] Michael : Yeah. So in a way no matter if it's even if it's not like, oh, we are a K-pop star, you probably think there is a significant influence on K-pop influence.

[00:04:28] Honey: Even the music we play in here is K-pop. Yeah.

[00:04:31] Michael : And you kind of have on the second floor, which is more male oriented. Yeah, more of a hip-hop vibe. Yeah.

[00:04:38] Honey: Yeah, very heavily, heavily influenced by Travis Scott. Yeah.

[00:04:44] Michael : That's cool. Um, okay, so last question is what what do you think Vietnamese people define as Korean style? If you could break it down into descriptive words, what is Korean aesthetic style?

[00:05:07] Honey: I think Korean, and if I think of Korean style, I think like they are very. Like diverse. They have a lot of different styles. Right? Depends on I don't know how to explain it, But when I think of Koreans that I think of like clean, very clean, very like, well put together kind of look that is like normal, like day, daily style for me, but for like, you know, K-pop or concert and stuff like that. Definitely different vibe, super colorful and, you know, stuff like that, I don't know.

SOYOUNG’s 2nd floor was for menswear and most decidedly the core of their hiphop ethos.

But my brain was making other connections as well. As I looked at the designs, my subconscious brain was making connections to the hip-hop-infused brand Greedilous by designer PARK Youn-hee, here exmpliefied by this shot I took at her Seoul Fashion Week runway show in September 2023.

While inside the SOYOUNG shop’s second floor, as I looked at the bricolage layering and the use of kitschy borrowings from other cultural iconographies that were just past the point of being gaudy or gauche, I was drawn to thinking of GREEDILOUS’s hypermodern aesthetic.

The namecheck of Travis Scott design sensibilities, in which the body is a medium for sartorial mixing and layering, got me thinking. [photo source]

Whether or not SOYOUNG and GREEDILOUS have a direct connection, the two brands do seem somewhat distinct from one another. But they do seem to exist within a shared universe of design imperatives — of cultural remixing, kitschy bricolage, and a powerfully obvious hypermodern aesthetic.

Might it not also be true that we have a Korean and Vietnamese designer who’ve arrived at similar conclusions at the receiving end of a hypermodern global set of pop culture aesthetics and sensibilities, with the two arriving at a similar yet separate set of semiotic conclusions?

Vietnamese consumers who shop at SOYOUNG aren't confused about cultural origins—they're demonstrating sophisticated understanding of how global cultural networks operate. They recognize that "Korean style" has become a trusted delivery system for accessing a constellation of bold, street-influenced aesthetics that originated in American hip-hop culture but have been refined and rebranded through Korean cultural industries. When they seek out "Korean fashion," they're not looking for traditional hanbok or distinctly, traditional Korean cultural elements; they're looking for the curated global aesthetic vocabulary that Korean cultural industries have successfully packaged under Korean branding.

Circle K's Vietnamese integration: My Tien (@_midnight_mt) inside the KTT’s Circle K that exemplifies successful foreign market entry and cultural adaptation. Since Circle K entered Vietnam in 2008, the American convenience chain has achieved 48% market share not through cultural dominance but through systematic localization — adapting store layouts, product selection, and social functions to Vietnamese usage patterns.

Vietnamese cultural actors aren't passive recipients of Korean cultural exports; they're sophisticated “cultural DJs” in their own right, sampling from global cultural vocabularies to create new combinations that serve local needs while maintaining connections to international networks. They understand that categories like "Korean," "American," or "European" function less as indicators of actual cultural origin and more as organizational frameworks for accessing different types of global aesthetic resources.

This has profound implications for how we think about cultural authenticity. If Korean cultural industries are themselves sampling from global sources, and if Vietnamese cultural actors understand this process and participate in it actively, then questions about what constitutes "authentic" Korean or Vietnamese culture become much more complex. Authenticity becomes less about maintaining pure cultural traditions and more about maintaining cultural agency—the capacity to make creative choices about which global influences to incorporate and how to adapt them to local contexts.

The KTT complexes serve as particularly powerful examples because they demonstrate how this process works at the level of spatial practice. These developments were originally designed as instruments of ideological transformation, intended to create "new socialist persons" through architectural control of daily life. But residents transformed them into instruments of cultural agency, using their spatial creativity to navigate between socialist legacies, traditional Vietnamese culture, and global market influences.

The modifications residents made to these complexes—the "tiger cages," the commercial conversions, the "squeezed-in construction"—represent alternative planning approaches that successfully blend residential and commercial functions, create affordable housing solutions, and maintain community resilience. Rather than viewing these modifications as problems requiring state intervention, they suggest models for culturally responsive urban development that transcend ideological boundaries while maintaining community-oriented spatial practices.

What emerges is a vision of cultural globalization that's less about domination and resistance and more about creative collaboration across cultural boundaries. Vietnamese spaces don't simply adopt Korean influences or resist American cultural imperialism. Instead, they function as active translation sites where multiple global cultural streams encounter local cultural practices to create new hybrid forms that are simultaneously international and distinctly Vietnamese.

This suggests that the future of global culture lies not in the dominance of any particular national cultural model, but in the proliferation of creative hybrids that emerge when culturally sophisticated local communities engage actively with global cultural resources. The most interesting cultural innovations may not come from traditional cultural production centers, but from places like those KTT complexes—spaces where different cultural systems encounter each other and generate unexpected combinations that no single cultural tradition could have produced on its own.

Conclusion: The Laboratory of the Future

That cat café, tucked into the ground floor of a socialist housing complex in Hanoi, turned out to be far more than a failed research site or an example of cultural misunderstanding. It was a window into how culture actually works in our globally connected world: not through simple transmission from producers to consumers, but through complex processes of translation, adaptation, and creative recombination that happen when culturally sophisticated local communities encounter global cultural resources.

The KTT complexes of Vietnam represent more than interesting examples of post-socialist urban development. They're laboratories for understanding how local cultural practices can maintain agency while engaging global influences—how communities can participate in international cultural networks while preserving distinctive local characteristics.

For researchers, the Vietnamese case suggests the importance of methodological flexibility and attention to unexpected convergences (Debord, 1958; Harms, 2013). The most significant insights often emerge not from following predetermined research plans, but from paying attention when different research approaches start connecting in surprising ways. When our research "fails" to find what we expected, it may succeed in revealing patterns we never would have discovered if everything had gone according to plan.

For understanding Korean cultural influence specifically, Vietnam reveals that the global success of "Korean" aesthetics may have less to do with the international appeal of specifically Korean cultural content and more to do with Korea's sophisticated capacity to function as a cultural DJ, sampling and rebranding global aesthetic elements under trusted cultural authority. This suggests that the most successful cultural exports may not be the most "authentic" national cultural products, but rather the most effective cultural translations that help local communities access global aesthetic vocabularies.

[IMAGE PLACEHOLDER: Final image showing the integration of multiple cultural influences in the Circle K]

For Vietnamese urban development, the KTT experience suggests supporting resident-driven initiatives that maintain community functions while adapting to changing economic conditions. Rather than viewing informal modifications as problems requiring state intervention, policy approaches might emphasize community-led upgrading, cultural preservation, and participatory planning that builds on residents' demonstrated capacity for creative spatial adaptation.

But perhaps most importantly, the story of that cat café points toward new ways of understanding cultural relationships in our interconnected world. Instead of thinking about culture in terms of national containers that either dominate or resist each other, we might think about culture as a collaborative creative process where the most interesting innovations emerge from encounters between different cultural systems.

The spaces I discovered in Hanoi—socialist in their planning principles, Vietnamese in their cultural practices, global in their aesthetic vocabularies—suggest that the future of culture may lie not in the preservation of pure traditional forms or the adoption of dominant international models, but in the proliferation of creative hybrids that emerge when local communities engage actively and confidently with global cultural resources.

In the end, that cat café that wasn't Korean taught me something crucial about how culture moves through our connected world: the most interesting cultural innovations may not come from the places we expect, and the most sophisticated cultural translation may happen in the spaces where different systems of meaning encounter each other and create something entirely new.

FINIto

AI Usage Statement

This article was written with significant assistance from Claude AI (Anthropic) in several specific capacities. The ethnographic fieldwork in Hanoi, the original discovery of the cultural translation processes occurring in KTT complexes, the development of the "Cultural DJ Theory," and all primary analytical insights about Korean aesthetic influence in Vietnamese socialist housing developments represent original human research. AI assistance was utilized for: (1) structuring the narrative following a Malcolm Gladwell-inspired, narrative discovery format while maintaining academic rigor; (2) conducting comprehensive literature review research on Vietnamese socialist urban planning and KTT housing complexes; (3) synthesizing complex theoretical frameworks about post-socialist urbanism with accessible explanatory language; (4) organizing various field observations into coherent analytical arguments; and (5) managing APA citation formatting and reference compilation. The core theoretical contributions, methodological innovations, and ethnographic insights remain entirely the work of the human researcher, with AI serving as a research and writing assistant to enhance clarity and accessibility without altering the fundamental scholarly arguments or discoveries.

This disclosure follows emerging standards for AI transparency in academic and online publishing. As institutions including Stanford University (Stanford University Press, 2024), MIT, and the University of California system have begun requiring explicit documentation of AI assistance in research and writing, such statements are becoming standard practice for maintaining scholarly integrity and reader transparency (Office of Community Standards, 2024; UCSB Writing Program, 2024). Stanford's AI at Stanford Advisory Committee specifically emphasizes that "whenever somebody uses AI, even if the AI does some work, they need to take responsibility for the output" (Stanford Report, 2025). These usage statements represent part of broader efforts to establish ethical guidelines for AI integration in academic work while preserving clear attribution of original human intellectual contributions, as recommended by academic institutions transitioning from case-by-case instructor discretion to systematic institutional policies (Duke Learning Innovation, 2025; Teaching and Learning Hub, 2024).

References

Choi, J. H., Foth, M., & Hearn, G. (2009). Site-specific mobility and connection in Korea: bangs (rooms) between public and private spaces. Technology in Society, 31(2), 133-138.

Debord, G. (1958). Theory of the dérive. Situationist International, 2. Translated by Ken Knabb, Bureau of Public Secrets.

Duke Learning Innovation. (2025). Artificial intelligence policies: Guidelines and considerations. Duke Learning Innovation & Lifetime Education. https://lile.duke.edu/ai-and-teaching-at-duke-2/artificial-intelligence-policies-in-syllabi-guidelines-and-considerations/

Glossy. (2021, February 11). Will K-fashion take off in the US? https://www.glossy.co/fashion/k-fashion/

Hurt, M. (2025). Top-line report: Cultural translation in Vietnam. KARSI – Korea Advanced Research Studies Institute. https://www.karsi.org/articles/topline-report-cultural-translation-in-vietnam

Kim, G. (2015). The aesthetic, the ordinary and the political: The Korean Wave and cultural policy in East Asia. Journal of Asian Studies, 74(3), 561-581.

Le, V. H., & Nguyen, V. T. (2020). Persistence of the socialist collective housing areas (KTTs): The evolution and contemporary transformation of mass housing in Hanoi, Vietnam. Journal of Housing and the Built Environment, 35(2), 531-555.

Lie, J. (2015). K-pop: Popular music, cultural amnesia, and economic innovation in South Korea. University of California Press.

McGee, T. G. (2009). Interrogating the production of urban space in China and Vietnam under market socialism. Asia Pacific Viewpoint, 50(2), 228-246.

Mytour. (2024, December 8). Top 10 shops for beautiful Korean-style dresses in Ho Chi Minh City. Mytour.vn. https://mytour.vn/en/blog/bai-viet/h2-class-text-center-top-10-shops-for-beautiful-korean-style-dresses-in-ho-chi-minh-city-h2.html

Mytour. (n.d.). Top 11 street style clothing shops for a trendy summer look in Hanoi. Mytour.vn. https://mytour.vn/en/blog/bai-viet/top-11-street-style-clothing-shops-for-a-trendy-summer-look-in-hanoi-mytour.html

Office of Community Standards. (2024). Generative AI policy guidance. Stanford University. https://communitystandards.stanford.edu/generative-ai-policy-guidance

Saeji, C. T. (2018). Gangnam style, authentic Koreanness, and the discourse of cultural appropriation. Popular Music and Society, 41(3), 284-305.

Schwenkel, C. (2020). Building socialism: The afterlife of East German architecture in urban Vietnam. Duke University Press.

SilverKris. (2024, June 5). The hippest places to shop and eat in Ho Chi Minh City. Singapore Airlines. https://silverkris.singaporeair.com/inspiration/fashion-shopping/crafts-souvenirs/ho-chi-minh-citys-hipster-side-revealed/

Skinvestment. (2023, January 5). Shop the unique styles of LIBE: A must-visit Viet fashion brand. Lemon8. https://www.lemon8-app.com/@_skinvestment/7185002733907296769?region=sg

Stanford Report. (2025, January). Report outlines Stanford principles for use of AI. Stanford University. https://news.stanford.edu/stories/2025/01/report-outlines-stanford-principles-for-use-of-ai

Stanford University Press. (2024). AI policy. https://www.sup.org/about/ai-policy

Teaching and Learning Hub. (2024). Teaching in the AI era. Stanford University. https://tlhub.stanford.edu/docs/teaching-in-the-ai-era/

The Dot Magazine. (2021, November 5). Three women-owned and fiercely hip Vietnamese clothing brands you need to know. https://thedotmagazine.com/three-women-owned-and-fiercely-hip-vietnamese-clothing-brands-you-need-to-know/

Thomas, M. (2002). Dreams in the shadows: Vietnamese-Australian lives in transition. Allen & Unwin.

Trinh, T. H. (2019). Housing and urban development in Vietnam: Transformation and sustainability. Urban Studies, 56(14), 2970-2986.

UCSB Writing Program. (2024). UCSB Writing Program AI policy. University of California, Santa Barbara. https://www.writing.ucsb.edu/resources/faculty/ai-policy