The Architecture of Accidental Revolution: How a “Spaceship” and the ‘Gram Accidentally Democratized Korean Fashion Culture

Seoul Fashion Week Attendees at the SETEC Convention Center parking lot, where “street fashion” was relegated.

The Parking Lot era

In October 2007, a young woman in electric blue tights posed with her compatriots for my camera in the parking lot of Seoul's SETEC Convention Center. I wasn’t sure if she was attending the runway shows inside or not — she was part of the crowd gathered outside for what was then called "The Seoul Collection," a struggling fashion event so desperate for international attention that organizers eagerly distributed press credentials to just about any foreign blogger willing to cover the event.

The woman in blue tights represented something the fashion industry couldn't yet recognize: the future of global street style culture. Her aesthetic choices — neon stockings paired with white pumps, heavy smoky eye makeup that would have been considered excessive on Seoul's conservative streets — were being beta-tested by a sophisticated underground network of fashion enthusiasts organized through Daum cafés, Korea's primary platform for niche community formation before the arrival of international social media.

When Seoul Business Association officials questioned why I was "wasting time" photographing these "normal people" with "nothing to say about fashion" instead of covering the sanctioned shows inside, they revealed the fundamental misunderstanding that would define the next decade of Korean fashion culture. International fashion buyers I was bumping into at the event were already reading my documentation of Seoul street style as essential intelligence about emerging trends, while local fashion industry professionals dismissed the same cultural innovators as irrelevant spectators.

Back in 2007, when Seoul Fashion Week organizers questioned me for “wasting time” photographing ordinary attendees. Even as I firmly believed these were the most interesting people at the event, they were literal outsiders. Yet it would be these people who would flip the field in just a few years.

The parking lot scene embodied a perfect institutional contradiction: Seoul Fashion Week invited international coverage of Korean fashion innovation, then tried to prevent documentation of the most innovative Korean fashion happening at their own event. What officials couldn't see in 2007 was that those "normal people" standing outside were inventing visual languages that would reshape global popular culture, developing aesthetic frameworks that anticipated how humans would construct identity through digital screens in the coming smartphone era.

Two Seoul Fashion Week attendees in the parking lot loiter around the action at the SETEC Convention Center in 2011, back when not only did such fashion fans have no (physical) place in the event, there wasn’t even a convenience store to buy water or easy access to the bathroom — the street fashion people at the time were persona non grata.

Seven years later, those parking lot prophets would become the main attraction when Seoul Fashion Week moved to Zaha Hadid's Dongdaemun Design Plaza, transforming from unwanted spectators into global cultural leaders whose street style overshadowed the runway shows entirely. The architecture of accidental revolution was already in place in 2007 — it simply needed the convergence of the right structure and the right form of digitality to complete the cultural transformation that would follow.

The DDP Scene

The first time I ever met the then-high school model hopeful @lollipop_lollipp was at the DDP in October 2014, before Korean style had taken off across the world. She was part of the fashion fandom that just started showing up to the event to participate as much as to spectate.

In October 2014, already as Seoul's longest-shooting foreign fashion photographer, I found myself on the gleaming ramp of Zaha Hadid's newly opened Dongdaemun Design Plaza. For seven years, I had been documenting Seoul Fashion Week in "parking lots and lobbies" when the lines got too long for the main venues (Hurt, 2018). Now, I was watching something I had never seen before: Korean teenagers in elaborate outfits commanding more photographers than the runway models inside. One girl poses against the building's silver curves while a dozen cameras click. She uploads to Instagram immediately. By evening, her outfit will have more global reach than anything shown on the official runways.

I doesn't realize it at the time, but I was witnessing the exact moment when architecture and technology accidentally flipped the hierarchy of global fashion. Within three years, Seoul Fashion Week would achieve "top 7 fashion weeks in the world" status (Hurt, 2023), not because of its designers, but because of its democratized street fashion documentation. Google searches for "Seoul Fashion Week" now return almost exclusively street fashion photos, not runway shows (Hurt, 2019). International media outlets from Vogue USA to Women's Wear Daily cover Seoul Fashion Week primarily for its attendee style, rarely mentioning the actual designers (Hurt, 2019).

From my paper “From fashion fandom to phenom: The paepi as real hallyu. Korean Regional Sociology,” 20(1), 5-34. The pattern of coverage was unprecedented. Back in 2007 or so, SFW would do flips and dances to get any international press coverage — even a single story. Now, it was getting the coverege — but ironically, not much about the runway.

Korean Fashion's Accidental Revolution

This transformation represents what Hurt (2019) identified as "the amazing flipping of the stage of the fashion field." Seoul Fashion Week's move to the Dongdaemun Design Plaza caused what had been a fringe fandom relegated to the parking lot of the event to become the main “runway” for fashion week coverage. The traditionally invisible street fashion participants suddenly received more global media attention than the industry professionals the event was designed to showcase.

But why did this phenomenon occur specifically in Seoul, and why in 2014? The answer lies in the convergence of two forces that had been developing independently: architectural innovation designed for adaptability, and Korea's delayed but blazingly fast adoption of global social media platforms after years of digital isolation.

Before the move to the DDP, there were some in-between years, like when Seoul Fashion Week was held at the IFC Mall in Yeouido, and was split between shows held by the Korean Fashion Design Association, which had decided to splinter off and hold its shows separately in tents inside the Yeouido Park itself. Show attendees from the line pose and embody the fashion Zeitgeist of 2013.

Force One: Alien Architecture

The Dongdaemun Design Plaza, conceived by the late Zaha Hadid and completed in 2014, was initially dismissed by critics as an "egregious eyesore and a waste of taxpayers' money" (Yun, 2014). The building's fluid, metallic surfaces earned it the nicknames “alien” and "spaceship" from locals who saw it as an “abomination” against Seoul's urban fabric. However, Hadid's design philosophy contained a hidden catalyst for social transformation.

The DDP was designed using "parametricism," an architectural approach where the building's form — designed with parametric equations — adapts to the needs of its users rather than dictating fixed functions (Schumacher, 2016). Hadid conceptualized the structure as a "metonymic landscape" in which "each space is made unique and memorable in its articulation" and "the various diverse, and often very specific, audiences start to use the building" in ways the designers never anticipated (Schumacher, 2016).

By Seoul Fashion Week in 2019, the Dongdaemun Design Plaza ramp was arguably (and obviously) the largest fashion “runway” in the entire event, with more global, social media-connected, individual photographers than any formal runway inside the event. And this “runway show” goes on all day, every day, throughout the week.

This design philosophy proved prophetic. The DDP's most dramatic feature — a sweeping ramp leading from street level to the entrance — was intended merely as a circulation space. Instead, it became what Hurt (2018) describes as "a veritable pageant" for Korean street fashion participants. The ramp's metallic curves provided a more photogenic backdrop than any runway inside the building. Its accessibility meant that anyone could participate in the fashion spectacle, unlike the exclusive runway shows taking place inside the building.

Most critically, the DDP's parametricist design allowed what Hurt (2019) calls "the uses of the space to adjust to the needs of those occupying it." The building literally enabled the street fashion community to transform from spectators into the main attraction, creating what Hurt (2018) identified as the "unofficial main attraction of street fashion" that overshadowed the official Seoul Fashion Week programming.

A paepi attendee at Seoul Fashion Week in October 2017, standing outdoors yet covered by the building’s structure, underground yet with the sky visible and looming overhead, and within the official area of the event yet mingling amongst members of the public who still utilize the main street fashion “runway” ramp to access the subway stop there.

Force Two: The Digital Awakening

The second force emerged from Korea's unique digital development trajectory, characterized by sophisticated infrastructure combined with cultural and regulatory isolation from global platforms. For over a decade, Korean internet users lived in what technology observers called a "walled garden" dominated by domestic portals Naver and Daum (Korea IT Times, 2009). Google, which commanded 64% of searches in the United States, held only 3% of the Korean market as late as 2009 (Korea IT Times, 2009).

More critically, government-mandated technical requirements actively prevented global technology adoption. From 2005 to 2009, the Korean government required all mobile phones to include WIPI (Wireless Internet Platform for Interoperability) software, effectively blocking foreign smartphones including the iPhone (Korea Communications Commission, 2008). Foreign companies were "reluctant to produce WIPI handsets just for the Korean market," which represented only 20 million units annually compared to global scale (Korea Times, 2008). This regulatory protectionism meant that while the iPhone 3G launched globally in July 2008, Korean consumers had to wait until November 2009—an 18-month delay that Korea's largest newspaper called evidence of "how closed and outdated its communications market is" (Associated Press, 2009).

The convergence of these factors created what we might call Korea's "delayed digital awakening." When WIPI requirements were finally abolished in April 2009, Korea began a rapid transition from digital isolation to global platform integration. However, the cultural adoption of international social media platforms took several additional years to reach critical mass.

2014 proved to be the tipping point year. The National Institute of Korean Language officially recognized "mukstagram" — the practice of posting food photos on social media — as one of the year's most noteworthy new words (Korea Herald, 2017). The suffix "-stagram" unmistakably highlighted Instagram's cultural penetration into Korean daily life. Simultaneously, Korean smartphone adoption reached the critical mass necessary for ubiquitous social media documentation, growing from just 22% in 2011 to projections of 84.3% by 2016 (Statista, 2015).

This timing meant that Korea's sophisticated visual culture, developed through years of advanced internet infrastructure, finally gained access to global broadcasting platforms at precisely the moment Seoul Fashion Week moved to its ideal architectural stage.

Convergence: When Infrastructure Meets Access

The collision of architectural opportunity and digital capability created something unprecedented in fashion culture. Korea's newly Instagram-connected population didn't just gain access to global social media — they gained access at the exact moment they obtained the world's most photogenic fashion venue.

What emerged fits perfectly within Jin and Yoon's (2016) theoretical framework of "spreadable media practice" operating within a "social mediascape"—"the mediated space enhanced by the global distribution of social media" (p. 1279). Their analysis of Korean Wave cultural transmission in general identifies three critical dimensions that also converged at Seoul Fashion Week in 2014: technological affordances that enable user participation, participatory sociality that facilitates fan-driven content creation, and textual impurity that enhances cultural spreadability.

Korean street fashion proved to be an ideal "spreadable media practice" because it embodied what Jin and Yoon (2016) identify as "impure cultural forms" — hybrid aesthetics that blend "Western and local cultures" in ways that appeal to diverse global audiences (p. 1287). Street fashion participants weren't simply consuming Korean culture; they were actively creating what Jin and Yoon describe as "user-generated content" that other fans could "translate, circulate, revise, recommend, share, reframe, and remix" across global social media networks (p. 1285).

Digitally adept fashion people (“paepi”) permeated and merged with the space, posing and picturing and transmitting from within it, while its status as a public space made it a humane place where one could casually produce, rest, curate/create more, since the public is welcomed by being allowed to be present, along with being given access to bathrooms, shopping malls, and convenience stores.

The result challenged every assumption about how fashion influence spreads globally. Traditional fashion weeks operate through carefully controlled media access, with professional photographers documenting runway shows for industry publications and mainstream media. Seoul Fashion Week in 2014 became the world's first truly democratically documented fashion event, where participants were simultaneously performers and broadcasters of their own cultural phenomenon — exactly the kind of participatory culture that Jin and Yoon (2016) identify as central to successful transnational cultural flows.

Unlike Scott Schuman's pioneering street style photography, which began in 2005 and focused on individual subjects photographed by professional observers (Schuman, 2015), the Seoul Fashion Week phenomenon involved participants documenting themselves and each other for immediate global distribution. As Jin and Yoon's (2016) research reveals, social media transforms "hard media content, which is contained in a traditional media form, into soft, re-mixable, and spreadable forms" (p. 1285). The DDP's architectural democracy combined with Instagram's broadcasting democracy to create what Hurt (2018) calls a "completely new kind of social interaction and urban fashion culture" — precisely the kind of "social mediascape" that enables rapid transnational cultural transmission.

Most photographers go high; I go low. Fashion, from the ground up. A young fashionista from Hong Kong Kong at Seoul Fashion Week in October 2018.

This democratization had immediate global consequences. Korean street fashion began influencing international trends in ways that bypassed traditional fashion industry gatekeepers. Korean participants weren't waiting for international fashion media to validate their aesthetic choices—they were directly broadcasting to global audiences who could immediately adopt and adapt Korean fashion elements. This process exemplifies what Jin and Yoon (2016) describe as the shift from passive consumption to active cultural distribution, where "a wide range of media users are potentially shaping, sharing, reframing, and remixing media content in ways which might not have been previously imagined" (p. 1285).

Flipping the Field

As of Seoul Fashion Week in February 2024, the field remained flipped, with more points of entry for both models and photographers engaged in a form of cultural production that itself broadened the very definition of “model” and “photographer.”

The transformation's effects cascaded through multiple levels of fashion culture. At the institutional level, Seoul Fashion Week achieved unprecedented international recognition despite — or perhaps because of — its focus on street style rather than runway presentations. By 2017, Hurt's assessment placed Seoul at its self-set goal of being among the "top 7 fashion weeks in the world," a status achieved primarily through street fashion coverage rather than designer recognition (Hurt, 2023).

At the media level, international fashion publications began treating Seoul Fashion Week as essential coverage, but almost exclusively for street style content. Hurt's analysis of major Western fashion media coverage found that international outlets "rarely even mention high fashion designers in their rush to talk about the 'next level' interestingness of Korean fashion" (Hurt, 2019). The traditional media hierarchy — where fashion weeks existed to promote designers to industry professionals — had been completely inverted.

At the cultural level, Korean street fashion participants achieved something unprecedented: they became global trendsetters while remaining rooted in local cultural contexts. Unlike fashion bloggers who built individual brands, Korean street fashion operated as a collective cultural phenomenon where participants shared aesthetic innovations through peer networks amplified by architectural and digital infrastructure.

Baby Supreme in 2018.

The global fashion industry took notice. Women's Wear Daily planned to brand the event "WWD Seoul Fashion Week" in March 2020, before the COVID-19 pandemic interrupted international fashion coverage (Hurt, 2023). Major fashion brands began sending representatives to Seoul not to see Korean designers, but to observe Korean street fashion trends that could influence their global collections.

The Bigger Picture: Infrastructure as Cultural Revolution

The Seoul Fashion Week transformation reveals larger truths about how cultural power shifts in the digital age. Traditional cultural gatekeeping — whether in fashion, media, or other creative industries—depends on controlled access to distribution platforms. When distribution becomes democratized through both physical (architecture) and digital (social media) infrastructure, previously marginalized communities can become cultural leaders overnight.

This phenomenon extends beyond fashion. The same convergence of accessible physical spaces and democratic digital platforms has transformed everything from music festivals to political movements. The Seoul Fashion Week case study demonstrates that cultural revolution often occurs not through intentional activism, but through the accidental alignment of infrastructure capabilities with cultural energy.

The economic infrastructure component proves equally significant as the physical and digital elements. Unlike major fashion weeks in Paris, Milan, or New York that operate as privately funded, invitation-only industry affairs, Seoul Fashion Week's status as a government-funded cultural event created an unprecedented democratic requirement. Because the event relied on taxpayer-collected public funds, it was mandated to grant public access through ticket sales—operating, as one observer noted, "in rock concert fashion" rather than as an exclusive industry gathering.

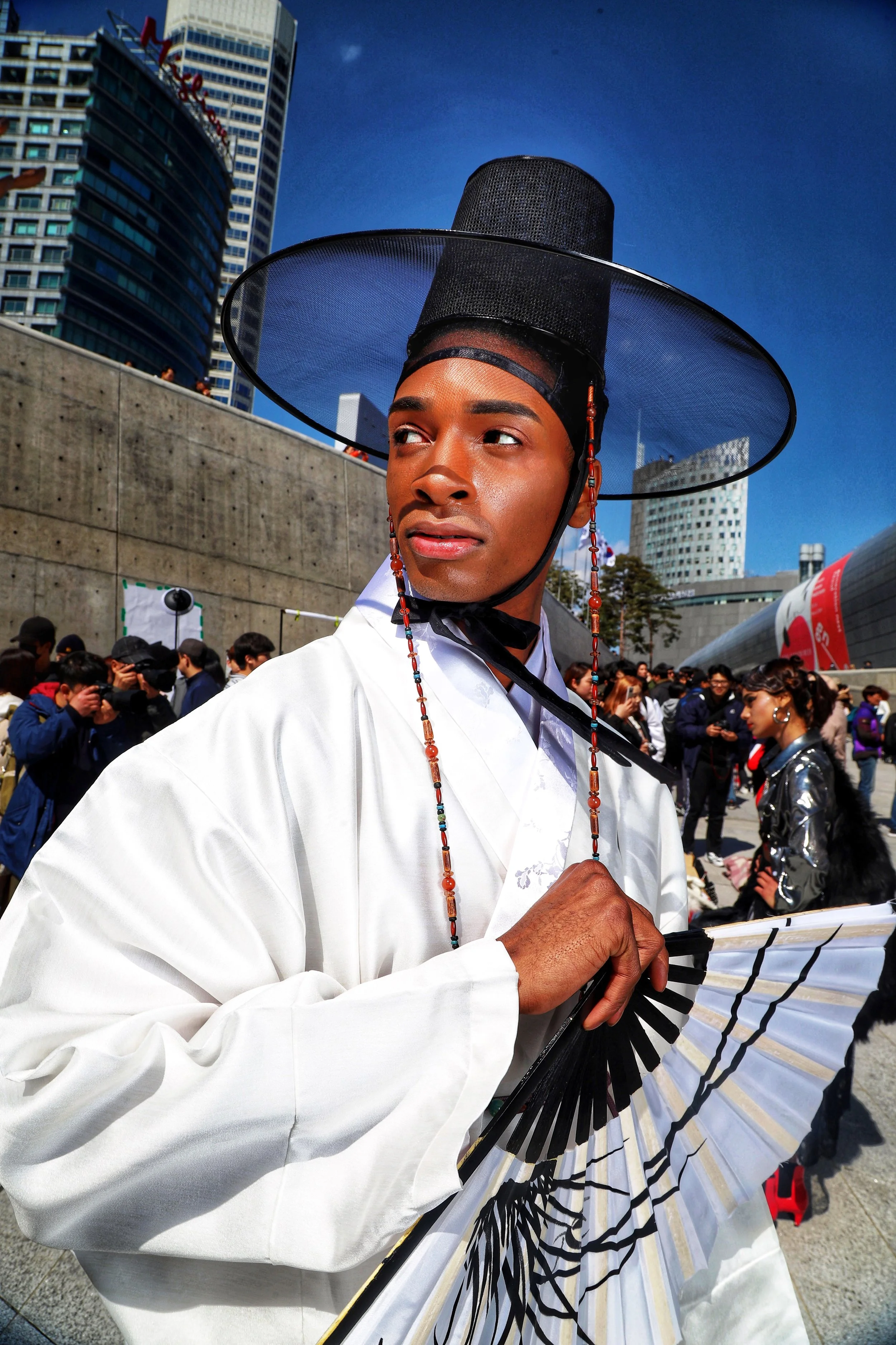

By March 2019, when Korean model (of mixed Nigerian/Korean descent) Han Hyun Min was already an item burning up the runway, Seoul Fashion Week had also democratized access to the runway itself, as it had then-recently started hosting open call auditions to the runways in the event, which allowed for a far greater diversity of faces and races than had ever beeen seen before, when all runway shows were gatekept by a few major agencies.

This economic infrastructure of public accountability fundamentally altered the cultural dynamics. Where other fashion weeks function as closed industry circuits designed to promote designers to professional buyers and media, Seoul Fashion Week's ticketing requirement created what amounted to a "photographic free-for-all" where high school students could mix with industry insiders, and anyone could approach stylishly dressed attendees for photographs. The public funding mandate accidentally created the most democratically accessible major fashion week in the world.

The architectural component proves particularly significant. The parametricist design philosophy — which allows spaces to adapt to user needs rather than imposing fixed functions — enabled cultural transformation that traditional architectural approaches would have prevented. The DDP's success suggests that future cultural infrastructure should be designed for adaptability rather than control.

Also of note is the fact that housing the entire fashion week event inside the bowels of the behemoth DDP structure creates a kind of singularity and unity that other international fashion weeks (save for Vietnam’s) tend not to have. Most other fashion weeks in major world cities are spread across the city, divided into a maze of multiple venues that inevitably make the event harder to navigate and cover. This is another crucial aspect of SFW that must be considered as part of the event’s unique recipe for success. In combination with the event’s extremely sudden and complete digitality.

By March 2019, @lollipop_lollipp (the young high school-aged model who starts off this article) had grown up and gone on to become a successful, popular, and enormously talented model whom I would constantly bump into on the DDP’s Ramp of Fashion Democracy. She was difficult to pin down for even this shot because, as she explained, she was in ten SFW runway shows that season.

The digital component reveals how delayed adoption can sometimes create more explosive cultural changes than early adoption. Korea's years of digital isolation meant that when global platforms finally gained traction, they encountered a sophisticated visual culture ready to make immediate global impact. Other culturally rich but digitally isolated regions might experience similar revolutionary moments as global platform access expands.

The convergence of these infrastructural elements— economic accessibility mandated by public funding, architectural adaptability, the unified nature of the event and delayed digital democratization — created the conditions for a cultural revolution that no single factor could have achieved alone. The public funding requirement ensured diverse participation; the parametricist architecture enabled unexpected cultural uses; and the delayed digital adoption meant that a sophisticated local fashion culture was ready to explode globally once barriers were removed.

Model @lollipop_lollipp as one of the main, favorite models for brand Graphiste Man. G’s runway show in Seoul Fashion Week in October 2019.

Implications for Cultural Democracy

The Seoul Fashion Week transformation suggests that cultural democratization requires more than just access to communication tools. It requires the convergence of architectural spaces that enable participation, digital platforms that enable distribution, and cultural communities ready to take advantage of both.

This convergence model might inform future cultural development strategies. Rather than focusing exclusively on elite institution building or digital infrastructure development, cultural planners might consider how to create conditions for accidental cultural revolution—spaces and platforms that can adapt to unexpected cultural uses by previously marginalized communities.

The Korean experience also demonstrates that cultural isolation, while limiting in some ways, can preserve and strengthen local cultural traditions that become powerful once global distribution becomes available. Korea's fashion culture wasn't created by global influence—it was refined in isolation and then explosively distributed once barriers were removed.

Conclusion: The Architecture of Accident

Model @lollipop_lollipp, whom I have come to consider the Herald and Harbinger of Seoul Fashion Week’s digital, democratic denouement at the Dongdaemun Design Plaza.

The Seoul Fashion Week transformation of 2014 wasn't planned by architects, government officials, technology companies, or fashion industry professionals. It emerged from the accidental convergence of architectural adaptability and digital democratization at the moment when Korean cultural energy was ready for global expression.

Model @lifesopastiche on the newer, more diverse, social runway of Seoul Fashion Week at the DDP, which is itself a “metonymic structure” that represents Korean society itself. Where people of all stripes can participate in defining the content that constitutes what it means to be “Korean.”

This "architecture of accident" suggests that the most significant cultural transformations may occur not through intentional innovation, but through the unintended consequences of infrastructure decisions. Zaha Hadid didn't design the DDP to revolutionize fashion culture. Instagram wasn't developed to amplify Korean aesthetic influence. Korea's delayed digital adoption wasn't intended to create explosive cultural convergence.

Yet these unrelated forces combined to create something unprecedented: a fashion week where former spectators became global cultural leaders, where architectural space enabled cultural democracy, and where digital tools amplified local culture into international influence.

As we consider future cultural development — whether in fashion, media, arts, or other creative fields — the Seoul Fashion Week case suggests that the most transformative infrastructure may be that which enables unexpected uses by unexpected users. The revolution, in other words, may be most likely when we build spaces and platforms that can be accidentally appropriated by the very communities we never imagined would become cultural leaders.

Model @lollipop_lollipp as Korean fashion culture’s herald and the product of the nascent, powerful fashion culture that produced her, and continues to explode with cultural force on the ramp behind her.

The accidental nature of this transformation doesn't diminish its significance. If anything, it suggests that cultural democracy thrives when infrastructure builders focus less on controlling outcomes and more on enabling possibilities. In Seoul in 2014, a controversial building and a delayed social media adoption accidentally created the conditions for fashion democracy. The question for future cultural development is not how to replicate this specific outcome, but how to create conditions where equally unexpected cultural revolutions might be able to emerge.

Model @joytv__ refracts the new, global interest in things joseon in October 2019 on the most diverse and intensely democratic global contact zone in Korea — the DDP ramp during Seoul Fashion Week.

Finito.

AI Usage Statement

This research paper was developed through collaboration with Claude AI (Anthropic) to synthesize primary ethnographic research, academic literature, and digital sources into a cohesive narrative analysis. The AI assisted with: (1) literature review organization and analysis, (2) structural development of the Gladwell-style narrative framework, (3) integration of multiple data sources and theoretical frameworks, and (4) editing and citation formatting. All primary research insights, theoretical frameworks, and conclusions remain the intellectual property of the author. The AI served as a research and writing assistant to enhance the presentation of original ethnographic work and academic analysis.

References

Associated Press. (2009, November 27). Apple's iPhone set to make splash in South Korea. Physics.org. https://phys.org/news/2009-11-apple-iphone-splash-south-korea.html

Hurt, M. W. (2018). Seoul Fashion Week and its hypermodern youth. Medium. https://medium.com/deconstructing-korea/seoul-fashion-week-and-its-hypermodern-youth-b169598049d6

Hurt, M. W. (2019). From fashion fandom to phenom: The paepi as real hallyu. Korean Regional Sociology, 20(1), 5-34.

Hurt, M. W. (2023). How to kill a fashion week: A public letter to the honorable mayor OH Se-hun. Medium. https://medium.com/the-korean-style/how-to-kill-a-fashion-week-5fe6d5787dcc

Jin, D. Y., & Yoon, K. (2016). The social mediascape of transnational Korean pop culture: Hallyu 2.0 as spreadable media practice. New Media & Society, 18(7), 1277-1292. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444814554895

Korea Communications Commission. (2008, September 9). WIPI requirements for mobile handsets. Korea Times. http://www.koreatimes.co.kr/www/news/tech/2008/09/129_30830.html

Korea Herald. (2017, January 1). Instagram solidifies position in Korea. Korea Herald. https://www.koreaherald.com/article/1194089

Korea IT Times. (2009, June 1). Daum, Naver: Gardeners in Korea's walled language garden. Korea IT Times. https://www.koreaittimes.com/news/articleView.html?idxno=3610

Korea Times. (2008, September 9). Apple's iPhone debut delayed indefinitely. Korea Times. http://www.koreatimes.co.kr/www/news/tech/2008/09/129_30830.html

Schumacher, P. (2016). Parametricism 2.0: Gearing up to impact the global built environment. Architectural Design, 86(2), 8-17. https://doi.org/10.1002/ad.2018

Schuman, S. (2015). The Sartorialist: X. Penguin Random House.

Statista. (2015, September 16). Share of mobile phone users that use a smartphone in South Korea from 2014 to 2019. Statista. https://www.statista.com/statistics/257033/smartphone-user-penetration-in-south-korea/

Yun, J. (2014). Construction of the World Design Capital: Détournement of spectacle in Dongdaemun Design Park & Plaza in Seoul. Journal of Asian Architecture and Building Engineering, 13(1), 17-24. https://doi.org/10.3130/jaabe.13.17